In memory of Ornette Coleman, who passed away on June 11th, we are presenting reflections on selections from his influential discography. The recordings presented here not in release order but rather grouped by our contributors. We look forward to your thoughts as well.

Something Else!!!! (Atlantic, 1958)

The very first Ornette Coleman album from 1958, with a very programmatic title and four exclamation marks. An album with Coleman on alto, Don Cherry on cornet, Don Payne on double bass and Billy Higgins on drums. Amazingly enough, we find Walter Norris on piano, an instrument that is not usually used by Coleman, because the use of chords forced the band too much into a straight-jacket. Even if the album sounds very very very accessible today, with recogniseable structures and soloing, early listeners will have sensed the tension between Ornette’s direction and the still conservative approach of his band members. The album has some fantastic compositions as “The Blessing”, “When Will The Blues Leave?” and “The Sphinx”. Today’s listeners will find nothing bizarre about the album, and catalogue it as bop. For an in-depth discussion on this album, read Ethan Iverson’s piece here.

Tomorrow is the Question! (Atlantic, 1959)

Dating from 1959, Tomorrow Is The Question! – with one exclamation mark – is a good continuation of Something Else!!!!, yet without adding much musically. The band is still not the right one to work with Coleman, with Don Cherry on cornet, and without a piano, but now with Percy Heath and Red Mitchell on bass, and Shelly Manne on drums. All good musicians, but not yet the ideal ensemble to take on Coleman’s adventurous music. The absence of a piano gives Coleman and Cherry more freedom to solo without being hampered by chord progressions.

– Stef

Ornette! (Atlantic, 1961)

When first encountering a vast and important discography such as Ornette Coleman’s, where do you start? For me, it came down to pure chance as, many years ago, I picked up Ornette! from the bargain bin at a local record store. As it often happens with albums that first open up a whole new world of musical expressions and strange idioms to the listener, it remains one of my favourite Ornette Coleman albums to date. Recorded shortly after Free Jazz, probably and objectively not one of Coleman’s best records, it still dazzles me with its extended pieces, aggressive and propulsive sound, and an exhilarating, childlike sense of discovery. It shows Coleman and his cohorts beginning to find focus as they explore new venues freed from rules and preconceptions.

Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation (Atlantic, 1960)

A record whose name today possibly supersedes the importance of the music itself. Free Jazz is still considered to be the one album that somehow defines Coleman’s music, at least to a larger audience, even if it’s not remotely as radical and unconventional as some of his later stuff. Historical importance aside, Free Jazz is a great, accessible yet powerful record that features a double quartet made of musicians that would go on to shape the face of jazz for decades to come. It still sounds immense today, even to spoilt ears, with powerful collective improvisations and clashes between horns laid atop an almost chaotic, complex but firm rhythm section.

Science Fiction (Columbia, 1971)

It’s impossible not to be nonplussed when confronted with the frenzied, electrifying music that Coleman and his varying, dynamic group push out on Science Fiction. A crossroads of sorts for Coleman (and his first record for Columbia), it fuses his earlier efforts with hints of what was to come. The album presents itself as an eclectic mix of influences and ideas, featuring pop-like vocals, recitation, musette playing, and swirling horns, but is also often dominated and formed by Charlie Haden’s visceral, liquid bass and by Billy Higgins’s and Ed Blackwell’s intense, focused and precise drumming. Science Fiction is yet another proof of how Coleman’s music was mercurial, ever changing, and with a penchant of defying conventions and fixed descriptions as the man himself.

– Antonio Poscic

Ornette on Tenor (Atlantic, 1962)

I remember asking a friend (another sax player) about this album many years ago, he replied, “It’s great, Ornette sounds just the same, but on tenor”, and he was right! Ornette on Tenor, recorded in 1961, is (or could be) the album that Coltrane wanted to record with Don Cherry, or that Sonny Rollins hoped to make when he recorded Our Man in Jazz. However it took Ornette to come up with the definitive album of freebop on tenor. This was his last record on Atlantic and I guess the end of the classic quartet – Jimmy Garrison replaces Charlie Haden on this one. At times Ornette sounds like Dewey Redman, with whom he worked later, using the tenor in a way that I guess must have influenced Dewey’s vocal approach. Although the compositions are slightly less ‘memorable’, the group swings through the music and interact together in a way that wasn’t on the earlier albums. After this Ornette disbanded the group and went on to form his classic trio.

The Empty Foxhole (Blue Note, 1966)

My second choice is the formidable trio record, The Empty Foxhole, recorded on Blue Note in 1966. This is another Ornette album that side-steps fans and critics understanding of his music. An album which has several oddities, it features his eclectic violin and trumpet playing, and also introduces us to his son Denardo on drums, only 10 at the time. In fact it’s an album that you probably either love, or you just don’t get! I love the purity of sound throughout, Ornette’s brittle alto, the screaming trumpet and the scratching violin on Sound Gravitation. It’s great to hear how Charlie Haden never faulters, keeping the music flowing, whilst Denardo adds-in rhythm and colour. In fact, I can imagine that back in 1966 this must have sounded very odd, but when thinking about modern free time players such as Nasheet Waits or Paal Nilssen-Love it all makes perfect sense now.

– Joe Higham

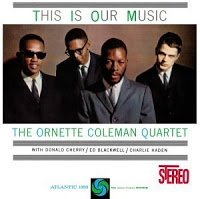

This Is Our Music (Atlantic, 1960)

Quite simply, this was my Rosetta stone, the album that decoded the potential freedoms of jazz by expressing them in the context of rules that had governed the music. Whilst all of the Atlantic period albums are of comparable quality and vie for pole in my affections, despite arguments for chronology this one pips them all. Ed Blackwell’s presence and the melodic swing it imbues, and the one-two of the cover and title, asserting a stance and attitude that this is our music on our terms.

Chappaqua Suite (Columbia, 1965)

Coleman strove to address the confines of both the music, and the perception of what a ‘jazz musician’ should be and could achieve. This soundtrack, ultimately unused for fear of being so beautiful it would overpower the film it was intended for, is a sweeping orchestral statement which places his ‘jazz’ trio in a context which absolutely validates Coleman’s assertion that he be considered as a composer, beyond the limiting stigma of his ‘jazz’ roots.

New Vocabulary (System Dialing Records, 2015)

It recent weeks it has become clear that this is a contentious album, it’s release having not been sanctioned by Coleman’s camp. However, the music within finds Ornette doing what he’d done time and again, finding a new way to frame his conception and express himself. To hear him guide his younger cohorts through areas which touch on the Dixon/Oxley ‘Papyrus’ recordings, or a skeletal Chicago Underground Duo, is sadly the final example of Ornette searching for new routes along the road less/untravelled.

– Matthew Grigg

The Shape of Jazz to Come (Atlantic, 1959)

Rarely

have a group of musicians – Ornette, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Billy

Higgins (now all departed) – reached such maturity in so short a time,

and under a title that from anyone else would have been monstrous

arrogance. The length of Ornette’s shadow has a reach over which few

have felt able to jump – there can’t be a jazz musician alive who hasn’t

learnt something from this album – and yet his playing was so singular

and his compositions so utterly unique that it’s often proved difficult

for others to avoid sounding derivative. The album contains tunes that

have become standards, most notably Lonely Women, one of the most

haunting melodies ever written, and Ornette’s most covered composition;

all the more surprising as it opens with two different pulses running

simultaneously: part of its spellbinding effect.

At the “Golden Circle” Stockholm, Volumes One and Two (Blue Note, 1965)

This Trio

toured Europe in 1965 – 1966 and although it hasn’t received the

plaudits of the earlier Atlantic quartets – possibly due to the limited

recordings that were made – it provided Ornette with arguably his most

flexible and responsive rhythm section: David Izenzon (bass) and Charles

Moffett (drums, percussion). As the sole melody instrument, Ornette’s

alto (with occasional violin and trumpet) was not so much exposed as

revealed in all its glory, showing how central the human voice was to

his playing – its cries, laments and laughter. Think of speech patterns

rather than bar line metre, and it all falls into place.

In All Languages (Caravan Of Dreams Productions, 1987)

A

good way to hear how Ornette’s two major phases relate, as eight of

these vignettes (only one lasts longer than four minutes) are covered by

both his acoustic The Shape of Jazz to Come quartet and the

electric Prime Time double-quartet (Ornette plus two guitars, two bass

guitars and two drummers) allowing side by side comparisons. Ornette’s

inspired melodic explorations — the range of places to which a tune can

be taken — are common to both settings, but the acoustic quartet has

the bonus of Don Cherry’s delicately chiselled contributions, Haden’s

perfectly weighted notes and the melodic contours of Higgins’ drums.

Prime Time, which was more about group texture than personalities,

throws Ornette’s playing into sharper relief as his agile lines dance

across the band’s glittering cross-currents.

– Colin Green

Twins (Atlantic, 1971)

An album of outtakes from the Atlantic years, Twins contains the first take of “Free Jazz” and a vehicle for bassist Scott La Faro called “Chalk Up,” which are probably the selling points; but the remaining three cuts almost outshine them. “Joy of a Toy” and “Little Symphony,” both from the This Is Our Music sessions, are full of light but challenging work, especially from drummer Ed Blackwell, who swings better than most hard bop players on their best days. The main theme of “Monk & The Nun” does its namesake justice while Don Cherry’s solo predates the type of runs Miles Davis would play during his electric years a decade later.

“AOS” from Yoko Ono’s Plastic Ono Band (Apple, 1970)

Yoko’s warbled cries bury Ornette’s crying trumpet warbles as an orgasmic climax turns homicidal on this rehearsal tape featuring Coleman’s band from 1968. (The band is Blackwell, Haden, David Izenzon & Coleman.) Ono’s cues lead throughout, making this more flux than free, and the piece ends with a few flying globs of phlegm in your ear.

Predates No Wave by eight or nine years.

Skies of America (Columbia, 1972)

Ornette’s grandest orchestral work, Skies of America conjures up beautiful (but stormy) landscapes that encompass every stage of the American dream – including the fear, greed, and white self-righteousness that resulted in the blood of Native Americans and the horror of slavery. Is it any wonder that certain passages sound like Charles Ives scored a thunderstorm? I’m reminded of Ives and Duke and Partch and Moondog – iconoclastic brothers of Coleman’s in a cruel, intolerant world – whenever I listen to this recording; but mostly I think about how wholly compassionate Ornette was to sift through the history and the landscapes and the God and the shit of America and mold it into a work of un-pretty, difficult, unflinchingly honest beauty so that we might recognize ourselves in it – as equals.

– Tom Burris

‘Free Funk Workouts’

Three of my favourite Ornette Coleman albums are some of his lesser-known works. In particular, I’ve chosen three albums which all have Bern Nix & Charlie Ellerbee on electric guitars and Jamaaladeen Tacuma on bass. Combined with Ornette’s unique harmolodic approach these three excellent albums whip up a free funk that still sounds as fresh as the day it was recorded.

Body Meta (Artists House, 1976)

Recorded before the Dancing In Your Head album but released after it, this was a new and welcome departure for Coleman, who yet again dared to do something different. His horn sounds at home amongst the angularities of the guitars and the funky bass, which is rhythmically delineated by the drumming of Ronald Shannon Jackson. A gem in his back catalogue that surely now deserves a long awaited re-release.

Of Human Feelings (Antilles, 1982)

This album features similar personnel to Body Meta but this time with two drummers. Released under his own name again but practically a Prime Time album where four to the floor disco beats mix it up with heterophonic melodies. This is a right royal funkster that is as dense at times as it is downright groovy.

Opening The Caravan Of Dreams (Caravan of Dreams, 1983)

This live album billed as ‘Ornette & Prime Time’ features Coleman fronting the full two guitars, two basses and two drummers line-up. There are six originals on this that show why they were THE ‘free funk’ band. Sharp contrasts of simple riff-based melodies, chaotic sounding textures, free blowing and more spacious interplay makes this album a great document of Ornette’s music around this period.

– Chris Haines

Beauty is a Rare Thing – The Complete Atlantic Recordings (Rhino/Atlantic Jazz Gallery, 1993)

By

the time that this box was released Coleman’s legendary quartet music

did not sound radical or revolutionary, at least not to me. Still it

taught me a lot about freedom, beauty and love. Even today, I am still

fascinated by its intuitive melodic, its impeccable rhythmic drive and

its urgent passion and joyful spirit. The music radiates a great need to

shout – I, we, the quartet – found a new sound, beautiful sound, and

our search for this sound was, still is, so liberating and full of joy.

– Eyal Hareuveni

Virgin Beauty (Portrait Records, 1988)

This

was my first Ornette Coleman album, which I purchased because

of guest guitarist Jerry Garcia (I was in college, it was the early 90s,

and I had much to learn). I didn’t get it at first – the music was

often frenetic, the rhythms funky but the harmonies didn’t conform

entirely to what I had been conditioned to – and it took a little while

for me to really hear it. “Three Wishes” has a single note motif that

repeats incessantly and devilishly as the music pivots around it. The track ‘Chanting’ is a lovely

ballad with Coleman on trumpet, and Garcia contributes flair to three of the tracks, like on ‘Singing in the Shower’ over its

‘Shakedown Street’ like riff. The band is a double quartet with

guitarists Bern Nix and Charlie Ellerbee, electric bassists Al MacDowell

and Chris Walker, and drummers Denardo Coleman and Calvin Weston.

Crisis (Impulse, 1969)

Crisis

is a live album recorded at New York University in 1969 featuring

Charlie Haden, Don Cherry, Denardo Coleman and Dewey Redman. It’s kin to

Broken Shadows and Science Fiction (or, the Complete Science Fiction) and is an out-of-print gem. The musical program features Haden’s ‘Song For Che‘ which simply levitates from the grooves and beautiful renditions of songs like ‘Trouble in the East‘.

Just listen to how the peaceful flute-work that opens the piece is

shattered by the saxophone, then coalesces into a frantic dance. The

seemingly politicized album cover, sporting the Bill of Rights burning with

the title printed starkly on it, is nearly reason enough to seek it out.

Song X (Geffen, 1986)

It’s

old news now, but Ornette Coleman and Pat Metheny’s collaboration was a

surprise. The guitarist can be a bit saccharine at times but then

comes up with brilliant project like Song X. The album was

recorded with bassist Charlie Haden (who worked with both Coleman and

Metheny) and drummers Denardo Coleman and Jack DeJohnette. The music is

Coleman originals along with some mutually penned compositions. I think

what Allmusic

says captures it best: “Metheny often manages to be a quite expressive

second voice, racing along beside the master saxophonist, offering

alternative strategies and never showboating… and in fact, the album

also contains some of Coleman’s best work since the mid-’70s.”

– Paul Acquaro

Change of the Century (Atlantic, 1960)

The record which revealed to me just how many chances a jazz musician could take and still swing. Yes, it’s true that this music doesn’t sound nearly as radical now as it did when it was released in 1960. But Coleman’s and Don Cherry’s playful leaps and heartfelt cries were (and remain) pretty adventurous stuff—and with the unfailingly nimble and fluid rhythm section of Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins, each cut still possesses an irresistible groove. “Ramblin’” in particular is an all-time classic and a superb representation of Coleman’s most accessible work.

Soapsuds, Soapsuds (Artists House, 1977)

In a duet setting with Charlie Haden, Ornette’s melodic side comes to the surface with arresting passages of lyrical beauty. The dialogue between the two musicians is stunning on these five tracks, and the recording quality is superb, particularly noteworthy as it highlights Haden’s outstanding bass playing. This is now out of print, unfortunately, but certainly worth getting for the sheer joy of hearing Coleman stretch out on pieces that are consistently expansive and explorative.

Sound Grammar (Sound Grammer, 1996)

Released in 2006, ten years after his previous record (Sound Museum: Three Women), this worthy document reminded all of us of Coleman’s continuing vitality at a youthful 75 years of age. With an astonishingly tight group, consisting of Denardo Coleman on drums and two bassists (Greg Cohen and Tony Falanga, the latter heard to exceptionally fine effect on arco), Sound Grammar showcases Ornette in a live performance of mostly classic Coleman repertoire, and the energy and sense of adventure that define each track more than justify the record’s winning the Pulitzer Prize in music that year. The rendition of “Song X” that closes the record is at times jaw-dropping in its group cohesion and righteous fury.

– Troy Dostert