The passing of pianist Paul Bley is a tough way start to the New Year, especially coming after the loss of Ornette Coleman this past summer. Fortunately, Bley leaves behind a massive and masterful discography. As a tribute, we present some of our favorites:

Paul Bley Quintet – Barrage (ESP Disk, 1965)

Recorded in 1964, shortly after the historic “October Revolution in Jazz” concert series in New York, the power and incision of this quintet cuts through the slightly muffled sound, on which Bley is joined by Dewey Johnson (trumpet) Marshall Allen (alto saxophone), Eddie Gomez (double bass) and Milford Graves (percussion). Ornette is a pervasive influence, in both the way the tunes are rattled out in abbreviated unison at the outset and close of each piece, and the hyperactive ‘barrage’ of the ensemble, at times sounding like Ornette’s Free Jazz, compressed onto the head of a pin. The aptly named ‘Batterie’ is a sign of Graves’ contribution, he and Gomez providing a bubbling platform for the solos, never allowing the music to settle. The compositions are all by Carla Bley, and the quintet manages to calm itself for one number, the lovely ‘And How the Queen’. The introspective side of Bley’s music would predominate in later years, with only occasional flashes of this kind of revolutionary fervour.

Paul Bley Trio – Blood (Fontana, 1966)

My pick from the ground-breaking piano trio albums recorded by Bley in the Sixties, where he’s joined by Mark Levinson on double bass (of later hi-fi fame) and Barry Altschul, drums. Bley showed an alternative means of musical development from the trios of Bill Evans, unpicking a tune and playing with its components in unpredictable ways – odd directions, digressions, after thoughts, even second thoughts – but so that the tune remains just visible, like a figure in a cubist painting (Bley’s Picasso to Evans’ Matisse). There are times when the music seems tempo free, even at a standstill; on other occasions different tempi are superimposed, something Bley would exploit further in his later music, particularly his solo performances. The trio performs as a unit, alert to every change in light and shade. This kind of playing was to prove influential to pianists like Chick Corea and Keith Jarrrett, whose early work, along with much of Bley’s from this period, is now perhaps unjustly neglected

Bley spent much of his musical life in a continuing discourse with the songs of Annette Peacock, whose often elusive tunes, marked by sparse phrasing and acute dissonances, form the basis of all bar one of the pieces on this album (the title work is a collective improvisation). He’s joined by bassist Gary Peacock – a long-standing musical partner with whom he recorded a number of outstanding duo and trio albums – and Franz Koglmann (who suggested the project during the recording session) whose fragile flugelhorn and trumpet are ideally suited to these pensive renditions. As with Free Fall (Columbia, 1963) and Bley’s sessions the previous year, which produced In The Evenings Out There (ECM, 1993), we hear various permutations – solos, duos and trios – as well as alternative readings: ‘Touching’ opens and closes the album, first as a meditative study by Bley alone, at the end by the trio as a brief, ghostly lament. Elsewhere, the cool occasionally icy, detachment sometimes present in Bley’s playing is matched by Koglmann’s austere outlines, as the tunes are reduced to skeletal form, Peacock’s terse bass lines providing only a hint of warmth. Playing of such brevity serves to heighten the emotional content, however – intense feelings expressed with concision, made more powerful by virtue of the restraint.

Another inspired grouping by ECM’s Manfred Eicher – Bley with Evan Parker (tenor and soprano saxophones) and Barre Phillips (double bass) – a trio which might look odd on paper but whose combination of piano, reeds and bass invokes the Jimmy Giuffre 3 with Bley and Steve Swallow of thirty years earlier. At the traditional ECM dinner the night before the session everyone was agreed: they had no idea what they were going to play, and what we hear is more or less in the order it was recorded. The result is a set of mutually sympathetic pieces, Bley and Parker not just finding common ground but exploring aspects of each other’s music, with Phillips, who had played with both, providing additional dialogue. On ‘Sprung’ Parker’s tightly wound soprano line is mirrored in Bley’s glittering run on the piano, and ‘No Questions’ is one of Bley’s free form ballads, accompanied by Phillips’ velvety bowing, in which the piano’s piquant harmonies are set off by Parker’s flinty edgings on tenor. The trio recorded one further album: Sankt Gerold Variations (ECM, 2000) which is also recommended.

– Colin Green

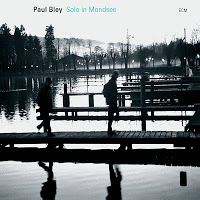

Solo in Mondsee (ECM, 2007)

Thirty-five years would pass between Bley’s solo albums on ECM, but when he finally returned with Solo in Mondsee, it was a revelation. Across ten “Variations” and more than an hour, Bley gives a master lesson in musical mediumship, channeling ghostly wisps from the entire history of jazz and blues. Unyieldingly lyrical and assured, Solo in Mondsee lays bare the essence of Bley’s musicianship, and would serve as a perfect introduction for anyone unfamiliar with his work.

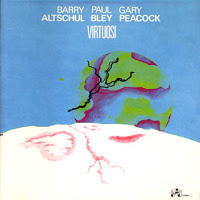

Virtuosi (Improvising Artists, 1976)

Calling an album Virtuosi may seem presumptuous, but there’s little denying how apt the description is, even without the benefit of hindsight. Recorded in 1967, the trio of Bley, Gary Peacock and Barry Altschul tackle two side-long Annette Peacock compositions. What’s virtuosic about the music is not its technical agility, but rather its remarkable restraint, the tunes unspooled in such a loose and spacious manner that they hardly seem composed at all. “Butterflies” floats as airily as its namesake, while Bley and Peacock trade leisurely melodies on “Gary.”

Time Will Tell (ECM, 1995)

Sankt Gerold (ECM, 2000)

These two albums, released five years apart but both recorded in the mid-90s, are an interesting communion of legendary musicians with very different approaches to free playing. Still, Bley’s unfailingly melodic touch dictates the terms of Time Will Tell: Parker is often miles away from the claustrophobics of his solo saxophone, and Phillips has a lush, deeply romantic bass tone. Sankt Gerold is more adventurous yet. Recorded in a booming monastery, Bley’s notes seem to ring on forever. While Parker and Phillips engage in frenzied chatter, Bley plays not a single unneeded note,and is all the more memorable for it.

– Dan Sorrells

– Tom Burris

Mr. Joy (Limelight, 1968)

Recorded live at the University of Washington in Seattle in 1968, Bley is on piano here, along with bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Billy Elgart. The music is generally upbeat, rather free and very accessible. There is one Ornette Coleman piece, ‘Ramblin’’, one Bley original – ‘Only Lovely’, and the other are penned by Annette Peacock. It’s a great place to get into Bley’s music – if you can get it – unfortunately it seems to be very much out of print.

The Paul Bley Synthesizer Show (Milestone, 1971)

Recorded in 1971, Bley is on the very early ARP synthesizer, electric piano, and piano. He’s is joined at various times by Dick Youngstein, Glen Moore, Frank Tusa, Steve Hass, and Bob Moses. The connection to the earlier album is the song “Mr.Joy”, which ends the album Mr. Joy, begins Synthesizer Show. Expectations need to be tempered a bit though, the sounds are quite primitive to 2016 ears, but its experimental nature was boundary pushing. Tunes like ‘Archangel’ and ‘Nothing Ever Was, Anyway’ are dark and absorbing, while ‘Parks’ is a nifty rock number. Also out of print.

Paul Bley & Scorpio (Milestone, 1972)

On this album, Bley is on a pre-Fender Rhodes on most of the album, though there are still occasional blips of synthesizer. With the rhythm section of drummer Barry Altschul and bassist Dave Holland, and a band name like Scorpio, you may expect something more pulsating like the music of Circle or Sam Rivers’ work, however aside from an incredible version of ‘King Kong’ and an effect laden ‘Syndrome’, most of the album is brooding and spacious. There are also a few other electronic keyboard and synthesizer recordings between these albums – Improvise, Dual Unity and a little later, Jaco. Paul Bley & Scorpio is available digitally.

Fragments (ECM, 1987)

Skipping ahead fifteen years, Bley made this beautiful quartet recording with Paul Motion, Bill Frisell and John Surman. According the liner notes, this was a hand-curated group by Manfred Eicher. Frisell’s tune ‘Monica Jane’ appears along Motion’s ‘For the Love of Sarah’ and Annette Peacock’s ‘Nothing Ever Was, Anyway’. Just from the opening moments, Surman’s rich tone and Bley’s considered sprinkling of chords you can tell something magical is afoot. The peak the quartet reached on Surman’s ‘Line Down’ is reason enough!

– Paul Acquaro