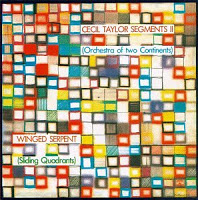

On Cecil Taylor Segments II (Orchestra of Two Continents)—Winged Serpent (Sliding Quadrants) (Soul Note, 1985)

Winged Serpent (Sliding Quadrants)

is one of the central moments in my education in free jazz and

improvised music. I was born in East Tennessee, lived in Nashville, and

grew up on a steady diet of country music and cornpone humor. As a

child, my parents took me to Shindigs where we saw all the big

stars—Billy “Crash” Craddock, Little Jimmy Dickens, Kitty Wells, Don

Gibson, Marty Robbins, Porter Wagoner, Dolly Parton, and “the Killer,”

Jerry Lee Lewis, whose curly mane the police physically removed from my

mother’s hands. I went to school with kids whose parents were on Hee

Haw. The mid-80s found me working at record stores in the mall when Punk

and New Wave had begun its awkward creep into Music City. When the

managers were away, I’d sneak some jazz on the turntable, much to the

displeasure of shoppers. I listened to a lot of Miles Davis and

Theolonius Monk. I studied the trajectory of Ornette Coleman. I read

biographies of John Coltrane and devoted mystical attention to his

records. My tastes grew increasingly avantgarde. When I started college,

I expanded my palette between classes in the library listening room.

Somehow, I got turned on to prepared piano and listened to all the Henry

Cowell and John Cage records. And it was in that room that I first

heard Cecil Taylor. Whatever prerequisites I was unconsciously trying to

make up for didn’t prepare me for the onslaught of Cecil Taylor, yet

somehow his sweeping swells of sound made perfect sense to me.

The Cecil Taylor album I have listened to most often in the last 30 years is Winged Serpent (Sliding Quadrants),

performed by Cecil Taylor Segments II (Orchestra of Two Continents).

This “orchestra” features a reed section composed of Jimmy Lyons, John

Tchicai, Frank Wright, Gunter Hampel, and Karen Borca. Andre Martinez

and Rashied Bakr play drums and percussion. Enrico Rava and Tomasz

Stańko are on trumpets, and William Parker plays bass. The cover art by

Claudio Rebaudo is 18 rows with 17 hand-drawn, variously colored and

shaded squares each. They abut one another in what seems to be a visual

representation of Taylor’s compositional strategies—a puzzle of “sliding

quadrants.” These musicians maintain the power and compelling unity of a

big band as they slide in and out of lines, patterns, and figures

orchestrated beforehand by Taylor or suggested by him on the piano in

the moment of playing. The percussionists keep even the most abstruse

moments connected to the cascading slipstream of things. The terms

“solo” and “group play” hardly seem to apply, or matter. What this album

demonstrates is how virtuosity reveals itself in composed sections and

in free improvisation. It’s like hearing everything all at once and

discerning music in what might have once just sounded like noise. I will

always be grateful for Cecil Taylor for teaching me how to listen and

what to hear.

– Rick Joines

Cecil Taylor & Günter Sommer – In East-Berlin (FMP, 1989)

I saw Cecil Taylor playing live only once. Taylor participated in a series of musical encounters titled From The Four Winds at the Israel Festival in Jerusalem on May 1987, playing solo and with drummer Andrew Cyrille. I still have the program that describes him as “the most gifted pianist among the jazz pianists of our times. He is as fast and quick as Art Tatum, strong as Bud Powell, and smart and devious as John Lewis”. The English version of the program called him the “Bartok of the jazz world”.

It was also the first time that I have listened, or more accurately experienced the Taylor phenomen. My musical experience until that time relied mostly on ECM albums (always available here) and some albums of Charles Mingus, John Coltrane.

The performance was a formative experience. Nothing made sense to me at first, the eccentric behavior, the dance steps, the poetry or the music itself – abstract, intense and often raging and wild. But soon enough I surrendered to this magical flow of sounds and his fascinating architecture of sonic textures. Taylor opened for me, as well as for many others at this performance, new means of listening, experiencing music as a powerful, liberating force.

Cyrille and Taylor did not speak at all on stage. Both came to the stage and left through different doors. Cyrille was no longer Taylor’s drummer of choice, and at times both sounded as confronting each other with angry, brutal determination, but at other times with touching compassion. There were times that Taylor sounded as the percussionist and Cyrille as the melodic, lyrical player. I was transfixed to every movement and my ears and eyes swallowed every nuance of these great masters.

Since then, I explored many of Taylor albums but always liked his duets with drummers. Always thought that he had a secret language with drummers. I cherish most his albums for FMP with Han Bennink, Paul Lovens, Louis Moholo and Tony Oxley but return again and again to the duo with Günter ‘Baby’ Sommer (who plays on the second album of this double album). Maybe because both masters stress here a great sense of jazz-y playfulness, dancing around each other, with great passion and joy. Maybe because I got to know Sommer about twenty years later on, enjoyed talking to him and his passion to make our world a better place. It does not matter. Take your time and enjoy this great album.

Cecil Taylor – Calling it the 8th (Hat Musics, 1983)

Many times it is difficult to speak of about a person who has just passed away, without having met him or her in person. But that’s what great about music, art in general: you get to know people, experience their feelings and opinions using this abstract, but usually so bold, language that we call music. And now I’m here trying to figure out what to say about one of the most important figures in jazz history.

I must admit that Cecil Taylor was the leading figure that persuaded me into accepting the piano as a key instrument in free thinking music. Before listening to his recordings and having spent a considerable amount of time listening to jazz standards where the pianist must do this and that and the other thing, the piano bored me. Yes, it did.

I came to listen to him through masterpieces of his art like Live At The Café Montmartre, Conquistador! and Unit Structures. So, when Paul Acquaro’s invitation came to write about a recording that made an impact on me came, the dilemma was big but pretty soon all was clear in my head.

Cecil Taylor was an innovator, a pioneer who took risks and fought his way when the music establishment was giving him shit. But you know all that and I’m not into repeating them. What really amazed me in his recordings was something else. It was his sensibility and flexibility, both two obvious qualities in 1983’s Calling it the 8th, that make for me this recording a landmark in his discography.

In addition to the above we must remember that Taylor, by 1983, had already a quarter of a century worth of a career behind him. He could easily stand and act as the big name, the leader of this LP. Not him. He is flexible enough and open minded to let time flow, make his presence as necessary as all the others (the great late Jimmy Lyons on sax, William Parker on double bass, and Rashid Bakr on drums), prepare himself to be the sticky tissue that united everything. You could say that when fine artists come together this can be too easy. Opposed to the latter argument I’d like to point out that even in collective improvisation big egos exist and they tend to suffocate each other.

Taylor, the great improviser, has the sensibility to lead each of these great artists into finding his own voice while, at the same time, helping out to produce a non-selfish language, a way to communicate their music all together. I don’t write these words to point out how great this quartet was. Not even how an important figure Taylor was among them. But merely to articulate just how he reacted to the other voices of his fellow musicians, the space they were allowed, the freedom they used to express themselves. Having been in the dirty music business far longer (only Lyons was also many years in the music business) that his three fellow travelers, Cecil Taylor seemed eager to react with them in an egalitarian, fruitful way. He was the driving force to combine talent and freedom, equality, personal expression and collective thinking.

That’s not just a great album but a lesson learned for life.

– Fotis Nikolakopoulos

@koultouranafigo

I had some initial trepidation entering the world of Cecil Taylor. For a while, I didn’t know much beyond the name, but a reflex purchase of Unit Structures and Conquistador! at a favorite shop of mine down the Jersey shore made for me that fateful leap. I was drawn to the intensity and clarity of his ideas, even if I didn’t exactly understand them. Seeing the graphical scores at the sweeping Whitney Exhibition didn’t help much either. Regardless, I was thrilled to have a chance to hear and see him in performance at the museum. Tipped off by a Facebook post, I found a ticket for the late added show and took in a performance that featured Taylor at the piano and reciting an epic poem (See Hank Shteamer’s excellent review of the show.)

Over time, I’ve found myself drawn to, and drawn back, to these albums:

Cecil Taylor – One Too Many Salty Swift And Not Goodbye (Hat Hut, 1978)

One day, I accidentally discovered a record store in Wilmington, DE where it seemed that someone dumped a treasure trove of Taylor and AACM related musical items. I scooped up as many as I could, and the most important was this LP box set with a bizarre title. As Martin mentioned in his tribute, the album was a recording of a concert in Stuttgart in 1978 with his working unit at the time. Not permitted to use the concert piano, Taylor performed on a slightly out of tune piano. This insult was seemingly channeled into fierce energy and the result was a masterpiece. The re-release on CD and digital (this is an easy one to find on mp3) added some tracks and changed the titles. The opening ‘Duet Jimmy Lyons/Raphe Malik’ features a spirited exchange between saxophonist Lyons and trumpeter Malik. Then comes ‘Duet Ramsey Ameen/Sirone’ between violinist Smeen and bassist Sirone, followed by ‘Solo Ronald Shannon Jackson’ featuring the drummer. Finally the main course begins: a sprinkle of notes from the piano, a blast from the horns, and they begin the slow build – about 10 minutes in it’s ablaze!

Oh, and it turned out that the copy of the LP I stumbled upon was signed by Taylor.

Cecil Taylor, Evan Parker, Barry Guy, Tony Oxley – Nailed (FMP, 2000)

Colin, a colleague here on the blog, turned me on to Nailed. It’s a stunning recording, again I reference Hank Shteamer who wrote in reflective piece about the album a few years back, he writes “There is something so magical about the outpouring of energy in these moments. You can’t get this anywhere else in life, this sort of incandescent freak-out. When it’s musicians of this caliber doing the freaking out, and you get to pay witness, it’s like seeing/hearing God.” There isn’t much more to say that can beat this description. I mean, look at that line up! Parker plays tenor sax on the album and while he drops out from time to time, his breath is fiery. Oxley is intense and his rapport with Guy is transcendental. The first moments of the 52 minute “First” sees Taylor jabbing notes in a lower register, while Guy bass rumbles along. Parker provides snippets of melody and Oxley at first restrains himself, but like the fraught moments of calm before the storm, something wicked (good) is brewing, and it hardly lets up for the duration. The group fragments at times, with intense duets/trios between the musicians but always comes together. One my favorite moments is about 16 minutes in on the second track “Last” where Parker is burning through the upper registers and Taylor is frenetically hammering at the keys, and Oxley is bashing away at the cymbals.

Cecil Taylor Feel Unit (w/Tony Oxley and William Parker) – 2Ts for a Lovely T (Codanza Records, 2002)

Again, I can exclaim “look at the line up” but that’s already been played. Regardless, Oxley and Taylor’s musical relationship goes back to the late 1980s, when they met for Taylor’s Berlin residency and made the recording Leaf Palm Hand (FMP, 1988), and Parker and Taylor have recordings going back to the early 1980s with Calling it the 8th (Hat Hut, 1986, recorded in 1981). So this set of recordings, released in 2002, documents the Feel Trio’s run from August 27 through September 1, 1990 at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London. It would seem at 10 CD’s that all of the sets from the engagement are here, and what you hear is a fine tuned group, engaging with each other at highly sensitive and empathetic level. The sets arc similarly from loose to dense and intense and finally to release at the end. How often can they do this without repeating themselves? Well, at least 10 times! The music exudes from them without hesitancy and features each member equally – Oxley and Taylor have a rapport that would suggest they had played together for much more than two years, and Parker finds the exact right tension and propulsiveness to demonstrate why he was indispensable to the trio.

PS – you can get the MP3s on Amazon for $11.

– Paul Acquaro