By Paul Acquaro

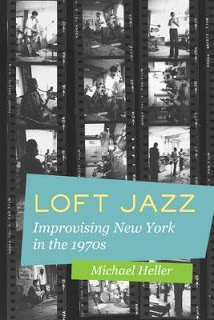

Michael Heller – Loft Jazz: Improvising New York in the 1970s (University of California Press, 2017) ****

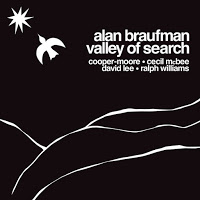

Alan Braufman – Valley of Search (1975 / 2018) ****

“So 501 Canal existed in quiet isolation in the midst of one of the biggest, most vital cities in the world. This was, and will always be, my New York. And in fall 1974, this is where Alan Braufman recorded his debut album, “Valley of Search,” a free jazz offering that embodies the city during this time.”