Albert Ayler Trio – Spiritual Unity (ESP-Disk, 1965)

By Nick Metzger

This album was my introduction to Gary Peacock’s playing and is among my

(and countless others) all-time favorites. Of course, the thing that struck

me on first listen was Ayler’s playing, but much of what makes it work is

in how the rhythm section reacted to it, and to each other. Peacock offers

impudent and angular lines that complement the metallic spray of Murray’s

continual torrent and an unsteady, visceral support for Ayler’s ecstatic

manifestations as they expounded a new way forward. That Peacock played on

this album in the same year he had a stint in Mile Davis’ quintet speaks to

the instinctive plasticity at the bedrock of his musical concept as well as

to the broad-mindedness of his nature. His playing always feels as though

it might unravel at any moment, building up tension, tumbling, but always

seemingly where it needed to be to buttress the strange and beautiful

floodgates of expression that commenced on that July day in 1964.

Lowell Davidson Trio – Lowell Davidson Trio (ESP, 1965)

Gary Peacock’s work with pianist Lowell Davidson and drummer Milford Graves

was very different from what he did later with Keith Jarrett and Jack

DeJohnette. From today’s point of view it seems almost unbelievable that

this album has remained Davidson’s only one (with the exception of a 1988

session with Richard Poole, which is available only digitally). From the

first notes of the opening track “L“ you immediately realise that this is

completely different from the trios of Bill Evans or Ahmad Jamal. Davidson,

who has composed all the music, uses space and timbre in a singular way,

his unheard-of, sudden changes of direction in terms of harmony and melody

are especially striking. The same goes for Peacock, whose style is much

rougher than later on, although there’s an inkling in “Stately 1“,

especially at the beginning, that his playing has also a penchant for

beauty and expanse. Even if Peacock almost has to fight against the

percussive rumbling of his bandmates, he suddenly rises up from a virtual

muffled silence for a solo passage. It’s like an echo of a forgotten pulse.

In the other longer composition, “Ad Hoc“, the piano rushes recklessly and

spreads into the universe, while Peacock contrasts this with a harsh solo.

Surprisingly, even the sound of Keith Jarrett’s trio is anticipated here

and there – at least in the melodic moments.

Lowell Davidson Trio was included in The Wire’s “100 Records That Set The

World On Fire (While No One Was Listening)“ list – when they expanded it

with 30 additional albums. It was hardly known until 1988, when it was

re-released as a CD. And even then it remained relatively obscure. For

those who don’t know it yet, now’s the time to discover.

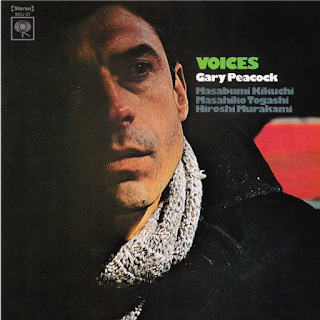

Gary Peacock — Voices (CBS/Sony, 1971)

By

Colin Green

Peacock shared a long friendship with pianist Masabumi Kikuchi with whom he

collaborated on many occasions over his distinguished career. They played

on several albums during his years in Japan, including Peacock’s debut as a

leader—Eastwind (CBS/Sony, 1970)—also featuring drummer Hiroshi

Murakami. On this session the same trio is joined by Masahiko Togashi on

percussion (he and Murakami each sit out one number). The album consists

entirely of compositions by Peacock, including the first appearance of two

of his most memorable that were to be reinterpreted on later recordings.

This sometimes deeply reflective music suggests an absorption of Japanese

culture, not just in the buzzing bass strings and pentatonic allusions of

the opening ‘Ishi’, but also in Peacock’s use of a dynamic space where each

note is weighed and phrase carefully articulated. There’s an architectural

solidity which remained a core feature of his playing and provided the

backbone for every ensemble in which he performed. Here, as on the brooding

‘Voice from the Past’, he is complimented perfectly by Kikuchi’s ink-wash

shadings and the illusive way the pianist draws out melodies, half-veiled

and half-revealed, set against Togashi’s filigree percussive curtain.

‘Requiem’ is a gentle lullaby, picked out by piano and bass over Murakami’s

dusky brushwork. The album closes with the animated ‘Ae.Ay’, driven by

propulsive bass and two distinct styles of drumming, jazz-inflected and

indigenous, which eventually dissipate into a colourful free exchange with

electric piano.

Peacock was to record further with Kikuchi, including six albums as the

trio Tethered Moon with Paul Motian on drums, a venture that covered music

by Hendrix, Kurt Weill, the songs of Édith Piaf, and adaptations from

Puccini’s Tosca (discussed by Lee below). Even within his favoured

format of the piano trio Peacock was a musician sensitive to many different

voices.

Ralph Towner – City of Eyes (ECM, 1989)

Paul Bley & Gary Peacock — Partners (Owl Records, 1991)

By

Colin Green

Paul Bley and Peacock had a lengthy and fruitful relationship, beginning

with their early days in New York where they were at the centre of the “New

Thing”, up to their final recordings with Paul Motian: Not Two, Not One (ECM, 1999) and When Will The Blues Leave (ECM, 2019). Described by Bley as “one

of those rare players you could always count on as playing better than

you”, rather than any of their trio recordings I’ve gone for this duo album

set down in 1989 which seems to capture their special rapport. Like the

subsequent Mindset (Soul Note, 1997) they play together and alone,

and as pointed out by Francis Marmade in the liner notes this is music

borne out of reciprocal listening and a respect for silence. A duo with the

pair locked in tandem leads to ruminative solos which in turn are

precursors to a duet of intimate exchanges, followed by further individual

studies, an alternating pattern of contrast and balance repeated at

different levels across the album.

Both are supremely melodic musicians, with a poetic understanding of how to

work tunes, many of which give the impression of having been invented on

the spot, often spawned from a simple figure, scale or combination of

chords, true instant composing. When it came to playing free Peacock saw no

meaningful distinction between composed and improvised material—it was more

a state of mind than a method—and I suspect Bley felt the same. There’s an

upbeat, homespun quality to the proceedings, drawing heavily on vernacular

roots, and celebratory rather than melancholy (for that, look elsewhere in

their catalogues).

Peacock had a way of combining a resonant, muscular tone with a fluid yet

very precise diction, heard to good effect in the opening duo, ‘Again

Anew’, that springs out of Bley’s deceptively simple but beautifully

elaborated theme. After waiting to hear what his colleague has to say,

‘Hand in Hand’ display’s Peacock’s ability to weave a counter melody

directly into the fabric of the music, always telling never ostentatious.

Other highlights include an animated take on Ornette’s ‘Latin Genetics’,

sprays of glittering bass harmonics (‘Gently, Gently’) and the miniature

piano suite ‘Afternoon of a Dawn’, blues drenched with maybe a hint of

Debussy in Bley’s arpeggios and subtle shifts in register, illuminated by a

lovely sounding Steinway. The closing duo is ‘No Pun Intended’, a

flickering dialogue between rattling bass and muted piano strings.

Gary Peacock and Bill Frisell – Just So Happens (Postcard Records, 1994)

Keith Jarrett – At The Blue Note (The Complete Recordings) (ECM, 1995)

Gary Peacock was famous for his work in piano trios, and the one with Keith

Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette was simply outstanding. The group had already recorded eight

albums with standards, when they performed three evenings at the New York

jazz club Blue Note in June 1994. Producer Manfred Eicher decided to record the performances for a unique sound

document from the first to the last note: on the six CDs that were produced

in the process, the trio proved not only their own versatility, they also

revealed the possibilities that these jazz standards offer. The repertoire

included 32 different Broadway, Hollywood and Tin Pan Alley pieces, jazz

ballads, bebop and swing numbers, as well as seven original compositions by Jarrett, some of which

were interspersed with the standards (for example the Charlie Parker number

“Partners“). What Jarrett had previously celebrated in his legendary solo performances, he succeeded in doing here

in collaboration with Peacock and DeJohnette. The improvisations, such as

“Autumn Leaves“, turn into epic monumental pieces of almost half an hour’s

length, revealing the trio’s full potential, its irrepressible wealth of

ideas. The fact that this was possible was largely due to Gary Peacock. The

way he slowly sneaks into “Desert Sun“ before his bass starts to roll after

two minutes gives the piece the irresistible knock-on effect that turns it

into a vortex. Peacock makes every new note sound like a discovery. There’s

no question: three masters are at work here. Playing jazz standards was

considered disreputable even for many jazz fans. This band freed it from boredom. In

their live gigs Gary Peacock was standing in the middle of the bandstand and this was not only

meaningful because most trios of this kind perform like this. This

arrangement made sense when Keith Jarrett stripped down the musical

framework of a composition in such a way that only a hunch remained: Then

Peacock’s bass used this open space, created contexts one would never have

thought of, became bold, adventurous and free without losing its pulse for

even a moment. He dances with his fellow musicians, for example in “You

Don’t Know What Love Is/Muezzin“. Or Peacock reduces his playing to very few notes, which he sets very precisely, like in the medley

of “I Fall In Love Too Easily“ and “The Fire Within“. Every note is an

anchor, a rescue station.

At the Blue Note – The Complete Recordings captures a unique moment in jazz

history. One of the best bands at the zenith of its career. Content and

creativity are preferred to habit and mechanical patterns, surprise to

routine virtuosity. The recording proves how you can say more with less.

It’s a mystery why this album trades under Keith Jarrett instead of

Jarrett/Peacock/DeJohnette – like so many others. Without Gary Peacock the

music of this band would not have been possible. These six CDs are among my

all time favorites, few albums have I heard so often. A masterpiece.

Tethered Moon: Gary Peacock & Masabumi Kikuchi & Paul Motian

Play Kurt Weill (1995)

Plays Jimi Hendrix+ (1998)

Chansons d’Édith Piaf (1999)

Experiencing Tosca (2004)

Gary Peacock always seems comfortably at home in piano trios, to the extent

that piano trio denotes a lineup more than a hierarchy of leadership. In

the case of Tethered Moon, the collaborative trio with Masabumi Kikuchi and

Paul Motian, there’s more than the usual dynamic improvisation, the three

generated a complete universe unto themselves. Half of their discography,

however, was given over to tributes. Tethered Moon, as a unit, wasn’t

content with merely playing the hits, so to speak. Over the course of nine

years, they bridged so-called high and low: opera, cabaret, and classic

rock. Plays Jimi Hendrix+ in particular takes the guitarist’s work and

completely transforms it. The thing to note here is there’s no

preciousness, the group takes Hendrix as seriously as they do Puccini, Piaf

as lightly as they do Weill. Peacock, Kikuchi, and Motian take each song as

a jumping off point, turning songs inside-out, bringing lightness and humor

to what, in other hands, might be fairly dry, humdrum homage. All this

music is putty in their hands, and Peacock exemplified the openness and

delight with which Tethered Moon approached all things. Peacock stood out

as a bassist for his technical skills, surely, but it’s albums like these

that really tell the story of his personality, his wit, and seemingly

bottomless love of music.

Amaryllis – Marilyn Crispell / Gary Peacock / Paul Motian (ECM, 2001)

Before she recorded for ECM, Marilyn Crispell had been interested in

exploring a more lyrical side of her musical personality instead of the

energy laden approach that had predominated previously. According to Crispell’s telling in this video, a friendship with

Annette Peacock arose in Woodstock and Marilyn was interested in doing a

project of her work, for which Annette immediately suggested Gary as an

accompanist. Crispell added Paul Motian to form a piano trio, asked Annette

to conduct since she was very particular about the dynamics of sections of

her compositions, and the project was immediately accepted by Manfred

Eicher. The resulting 2 disc set, Nothing Ever Was, Anyway. Music of

Annette Peacock was a critical success featured on many best of lists.

But the recording didn’t work for me as much as it did others. I needed

more Crispell playing Crispell. So the trio reconvened in Oslo with

compositions from each of the members, along with Manfred’s suggestion that

they play free ballads. Surprisingly to me, this was a new concept for

Crispell and in her words “a light went on” regarding how spontaneous

reactions could produce a composed sounding result. Gary Peacock usually

initiated things with a rich bass figure for which the others blended in

and built something new, including the Amaryllis title cut. Placement of

music is important both to Manfred and Crispell, and Peacock’s compositions

set the tone with “Voice From The Past”, “Requiem” and “December

Greenwings” interspersed in the first six cuts. Plus Peacock’s previous

backing of Keith Jarrett’s gospel influenced improvisations was brought to

play in Mitchell Weiss’s “Prayer”, which Crispell played in subsequent

concert appearances. Peacock participated in the realization of a new facet

of Marilyn Crispell’s music persona. Their relationship continued through

subsequent releases, notably the duet recording Azure providing a listener

friendly showcase for Gary’s instrumental prowess and sensitivity. But

after almost 20 years Amaryllis still draws me back.

Gary Peacock – Now This (ECM, 2015)

From the first noir moment of the opening “Gaia,” sprinkled with Copland’s pointillist touches, to the jubilant rendition of “Requiem” that closes proceedings on a high, Now This is predominantly sparse and solitary, inhabited by a sense of brooding lyricism anchored in somber bass tones. Throughout, both Baron’s and Copland’s playing remains subtle, often gently percussive. Their approach creates pockets of negative space for Peacock to sketch in tactile melodies with his double bass’s upper registers, gifting a pensive and introspective atmosphere to the music.

The record’s soft-spoken personality then lends further gravitas to those rare passages in which Peacock settles back into lower registers and locks into circular, ascending rhythms, releasing fleeting but freer, dissonant interplays between Copland’s scattered phrases and Baron’s bolder, signature rolls, which are so deeply felt on his collaborations with John Zorn. These segments complete and add just a bit of flourish to what is already a very pretty, silently dramatic album. A soundtrack for snowy winter days.

Gary Peacock Trio – Tangents (ECM, 2017)

When Gary Peacock recorded Tangents he was 82 years old and no longer had

to prove himself to anyone. He had been in the business for 60 years and he

was the formative bass player when it came to piano trios. Since 1983 he

played together with Jack DeJohnette in Keith Jarrett’s Standard Trio,

before that he played in the trios of Bill Evans, Paul Bley and Lowell

Davidson, but also with Masahiko Satoh / Masahiko Togashi and Marylin

Crispell / Paul Motian. Without any doubt he was one of the bassists who

gave the instrument a new role as an independent melodic voice, mainly

because he had always been a master of abstraction. And you can hear this

on Tangents, the last album of his own trio with Marc Copland (piano) and

Joey Baron (drums). Peacock seems to bring together all the experiences

from the other trios here, as if he were taking musical stock. On the one

hand he presents his own compositions like the dreamy “December Greenwings“

or those of his bandmates like the atonal “Cauldron“ (by Joey Baron) and on

the other hand they include two famous standards: Besides the classic “Blue

In Green“ by Miles Davis there’s also the melodic “Spartacus“ by Alex

North, both clearly refer to Peacock’s work with Jarrett. When you think of

typical (conservative) piano trio music this might be the sound you have in

mind.

However, Peacock is much more present on this album than in his trios with

the other pianists, one would almost be inclined to speak of a bass trio.

This becomes clear right at the beginning because “Contact“, the opener,

begins with a parading bass solo before Copland and Baron join in.

Everything revolves around Peacock’s flowing bass lines, piano and drums

only add single dots. “December Greenwings“ is particularly interesting on

this album, as Peacock has recorded it several times before: in 1978 with

Jan Garbarek for December Poems and then again in 2000 with Marilyn

Crispell and Paul Motian for Amaryllis. Arranged differently and recorded

with other musicians the piece shows a completely different quality, each

recording takes a new look at the same territory. The title track concludes

the album, and again Peacock reflects Marc Copland’s crystalline chords

with very sparing, minimalist tones, short riffs and elegant runs. The

gloomy mood and the frayed harmonies are rather reminiscent of Paul Bley

than Keith Jarrett, whereby the music – quite typical for an ECM recording

– remains very open and gets room to breathe.