By Paul Acquaro

Last year, Jazz 2020, a scaled back and localized version replaced the venerable Jazz em Agosto for its traditional two weekends at the end of July and start of August. It was supposed to be the Covid-19 version of festival, but as we all know, 2021 hasn’t been the light at the end of the tunnel that we all hoped for, however at least Jazz em Agosto is back in an international form – even if the café and patio outside the concert halls are closed, there is no merchandise table, and health rules are firmly in place.

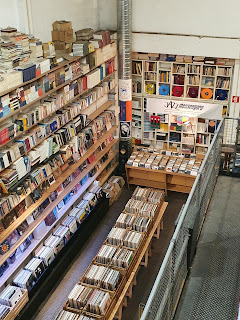

But, you ask, what about that merch? Every rabid collector scans for the table with that special one of a kind artifact. Well, this time around it required a hike to find it. I spent the day following the GPS on my phone, until I killed the battery, traversing the hills of Lisbon from the lush Gulbenkian Foundation grounds to the LXFactory, an 19th century textile factory, left to then molder, and now home to co-working, tapas, and tattoos. Tucked under the impressive 25 de Abril Bridge in Belem (a part of Lisbon a few kilometers out, along the river front), the former factory buildings are now home to galleries, restaurants, performance spaces, and to the fabulous Jazz Messengers record shop. This little gem, tucked into the upper level the building and accessed by gang walks, is surrounded by impressively obsolete printing presses and thousands of books belonging to the store through which you enter. The bookstore also houses a nice café that serves a cold beer to bedraggled city walkers like myself.

Jazz Messengers is a trove of (obviously) jazz and classical LPs and CDs, from mainstream (think Ella Fitzgerald, ECM) to the outer edges (think Relative Pitch, Trost) and many constellations between. They hold events – in fact, I was hipped to it by a social media mention of a gig by Lisbon saxophonist Rodrigo Amado and cellist Guilherme Rodrigues which happened earlier that week. (The concert, for those that are curious was given a rave review by the store’s owner – pointing to the high ceilings, she said it sounded like a cathedral.) Well, back to the point here, Jazz Messengers is the official shop for Jazz em Agosto, but because of Covid regulations, they cannot sell at the event. However, they have all the goods, from the LPs and CDs of groups playing (see the program here) and Jazz em Agosto branded T-shirt and LP tote bags. If you are in town for the concert, make the trek – you can do it by public transport, stupid little e-scooter, Uber (like the kids are doing it), or just walk it. I had the absolute pleasure of wandering through neighborhoods that I had not seen before, and chancing on places like the botanically exquisite Jardim Guerra Junqueiro.

Jazz em Agosto runs July 29th to August 8th, Thursday through Sunday, for two weekends. Sadly, the opening concert by Alexander von Schlippenbach, Peter Brötzmann and Hans Bennink – a free jazz super group if there ever was – was cancelled. So the first set of concerts started on Friday, with the 6 p.m. solo show from Lisbon based trumpeter Luis Vicente (see some reviews of Vicentes’ work). This was followed by a show from Broken Shadows, the brilliant alliance of the Bad Plus’ bassist Reid Anderson and drummer Dave King and the woodwind firepower of saxophonists Tim Berne and Chris Speed. The American group was a late replacement for the scheduled European group The End, which could not perform due to travel restrictions. Crazy times.

Luis Vicente

|

| Luis Vicente. Photo by Vera Marmelo – Gulbenkian Música |

Luis Vicente’s solo performance opened the set of concerts and, I would assume, some ears. Walking out on to the stage of the Gulbenkian Foundations smaller recital hall, it was simply Vicente and his instrument, no pedals, no effects, just some room reverb. He began playing with a slight fuzziness to his tone, creating a melody with a classical feel. Notes blended with other, sometimes tripping over each other, other times bursting into quick passages, sturdy tones sweeping gently, until splitting apart into polyphonics. Bifurcated and elongated tones then lead to a garden of extended techniques. It was a clever way to lead the us, the audience, into a personal universe of sound.

The trumpet has a particular set of sound properties, like any instrument of course, but the trumpet in particular has the sounds made by the embouchure, the valves, the air pressure, and the moisture. If you isolate these elements, they become like a bunch of parameters – add a little pressure, push the valves, change the lips’ position – that open up many possibilities. Sitting in the dark hall, looking at the musician on the stage, and immersed in this world, I imagined a multidimensional shape, a visualization of the data points, in the space between Vicente and us. Assured at the controls, the trumpeter formed beautiful and unusual figures in the air around him.

Of course, a large part of the art is in the arc of the performance: the sweeter sounds that drew us into his inner world, then the disassembly where the sounds were explored like the long moments of air, burbles of notes, and other ghostly tones. Then, piece by piece, they were reassembled in new forms, a more acerbic tone, the click of valves accentuating newly forming passages, a howl that bended with a human voice. Really, a magician at work.

Broken Shadows

|

| Broken Shadows. Photo by Vera Marmelo – Gulbenkian Música |

“It’s really nice to be here, it was very last minute,” said Tim Berne, taking a moment to engage the capacity audience. Then he deadpanned, “I just started playing the saxophone 3 days ago … I practiced a lot”

The four musicians, huddled in the middle of the expansive stage in Gulbenkians’ grand auditorium, had a lot of space to fill, and they did not shirk from their responsibilities. Indeed from the fierce opener, bespectacled white haired older gentlemen were exclaiming ecstatically in the rows before me, respectable citizens were bopping their heads, ready to explode into enthusiastic applause after the somewhat frequent bar-raising solos. Broken Shadows plays the music of Ornette Coleman, Charlie Haden, Dewey Redman, and Julius Hemphill, and thank god they are doing it. One song after another, each one a classic in its own way, erupted from the stage.

Song after song, the feeling hit “I know this song, what the hell is it called again?” Arrangement by arrangement, the commonalities of the songs, their structures and sounds connected in new ways. Perhaps that is the strongest component too, each song was recognizable, whether it was “Street Woman” or “Ecars” from Coleman, or “Body” from Hemphill, they feel like they are connected more than by this band that is lovingly taking these songs and imbuing them with new-found energy. Or could it, somehow, be the other way around?

Anyway, as the band began, the curtain parted behind the group revealing the lit-up tree-lined pond behind them. Themselves bathed in red and blue-green lights, wasted no time – a quick hit of that familiar melody and direct into explosive solos, while Anderson and King happily provided a tough but agile foundation. Berne’s alto climbed up and down the octaves effortlessly while Speed’s unfolding tenor playing provided a foil to the hard charging alto. The solos were often followed by a quick pivot back to the tune’s head and sharp bass slap and then done, onto the next.

The music was up-tempo to say the least, lithe, precise, playfully rambunctious, and above all infectiously enjoyable. Speed has a generally softer tone and seems to enjoy leaning into the enveloping bass lines, sometimes pouring out a stream of notes, other times letting a phrase linger in the air. Berne is pushier, his playing pulls slightly ahead of the beat, any number of ideas jostling each other for prominence. By the time you catch up with him, he’s sprinted ahead. Their contrast is fantastic.

When they launched into Hemphill’s ‘Dogon A.D.’, a new level of enlightenment was attained. The bass-line, originally a cello-line, is thrilling, as are the incisive snippets of melody interspersed between the lurching rhythm. The tune is a trek into a foreboding land: visceral, throbbing, and serious, it’s an intense work of art and in the able hands of Broken Shadows, none of the original dark energy is lost.

The work of this quartet is necessary. When Anderson performs the long introduction to Charlie Haden’s ‘Song for Che,’ we are hearing this ‘standard’ anew. When they play Julius Hemphill’s ‘Body’ or Ornette Colemans’ ‘Una Muy Bonita’, the melodies are strong, memorable, and the places they can lead the musicians to are stunning. Hopefully, Broken Shadows is laying down the foundation for others.

The final song (not including the quick encore of Dewey Redman’s ‘Walls-Bridges’) is pretty much a standard, as it’s been performed by many with varying levels of success. Yes, it’s Coleman’s ‘Lonely Woman‘. The crying saxes captured both the allure of the music – simple when you hear it, intricate when analyzed, and stunningly beautiful when done right. Broken Shadows did it right.

Fortunately, you can hear a damn good recording of the band playing the tunes described here on their recent eponymous Intakt Records release.

Ok Jazz em Agosto, looking forward to the next set of shows!