|

| Silent Green, Berlin |

By Paul Acquaro

Thursday night at Boulez Hall

minute bike ride, show our proof of vaccination, scan the tickets, peel off our

wet rain clothing, and find our seats. We were a bit frazzled by the time we

located our places in the upper balcony of the lush ovular hall. Through a light

clatter from the drums, a rustle of musical scores, and a few dolphin calls

emanating from the bass, we began to settle in. Then, the first notes from Swedish

pianist Bobo Stenson flowed from his keyboard and our nerves were quickly

subdued.The first night of the Jazzfest Berlin was off to a start.

The main part of the festival was at the Silent Green culture center about 8

kilometers from the classical music hall that this concert was taking place in.

The festival, which has been shifting and growing, extending and morphing over

the past several years, was back in person (an online), after being forced to be

entirely online last year, and spread out even further than before. The

constraints of the pandemic last year fostered a connection with Roulette in New York City, where a live stream connected the cities. This year, the idea

grew with live streams from concerts in South Africa (curated by Jess White

in Johannesburg), and multimedia contributions from Brazil (Juliano Gentile and

Manoela Wright for São Paulo) and Egypt (Maurice Louca in Cairo). In Berlin,

aside from the Silent Green, and tonight, Boulez Hall, the festival also would

be featuring the famous Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Charlottenburg, the nerve

center of former West Berlin. More about these locations later, now back to

Stenson’s trio.

|

Bobo Stenson. (c) Roland Owsnitzki / Berliner Festspiele |

The music was ebullient, but at the same time, reserved. This seems

to be the pianists trademark. Effortlessly, his melodies intertwined with Anders

Jormin’s bass bowing, and the bright – and sometimes humorous – responses from

Jon Fält’s percussive accompaniment. The trio, aside from some selected

favorites, was presenting a set of new music that will be recorded for an

upcoming ECM release next year. From gentle, slightly dissonant intros to

pulsating, vibrant crescendos, the trio’s work was refined and radiant.

|

| Kaja Draksler and Susanna Santos Silva. Photo by Roland Owsnitzki / Berliner Festspiele |

The duo of trumpeter Susanna Santos Silva and pianist Kaja Draksler

followed. The two have been performing together for a decent portion of their

lives and alhough from opposite ends of Europe, they share an obvious musical

affinity. At the Boulez Hall Steinway grand piano, Draksler began with a series

tightly coupled, short phrases, while Silva seemed to emit what I can best

identify as microtones. Both seemed equally as apart in their playing as

connected on the outer edges, which was quite a contrast to the previous set.

As their interplay continued, the duo engaged in ever more complex parallel

play, hitting dissonant intervals and unexpected harmonies. The pathos grew as

Silva’s long legato tones changed to explosive bursts, and Draksler’s began

traveling energetically up and down the keyboard. The improvisation turned

inward towards its end, for example, plucked notes from inside and outside the

prepared piano and the ‘pop’ of the mouthpiece extruded from the trumpet made up

an extensive passage.

|

| Vijay Iyer. (c) Roland Owsnitzki / Berliner Festspiele |

The final set was from pianist Vijay

Iyer’s trio that recently released Uneasy – namely the pianist with drummer

Tyshawn Sorey and bassist Linda May Han Oh. It also happened to be the first date of

their European Tour and Iyer’s excitement was palpable. “The pandemic,” he said,

“has given us chance to realize what’s important and playing for all of you is

it.” Setting an example, he continued “we may play masked, but our hearts are

open.”

US, but it’s not geographically limited) over recent years, but in concert,

the energy that the trio generated on the tunes was staggering. Iyer’s playing was lyrical and rollicking, Oh’s bass playing was

kinetic and as much a part of the melody as the support, and Sorey’s work was

that of the conductor of this mini-orchestra. Songs like ‘Combat Breathing’

and the war horse ‘Night and Day’ are powerful on the recording, and live,

nearly combusting. Any wisp of musical exhaustion after the first two hour of

music was whisked away immediately by the gale winds from the trio.It was still raining when the concert ended, but it hardly

mattered, we were gliding through the night.

Saturday night at Silent Green.

As noted, the festival is expansive. Covering multiple nights

and multiple venues, it’s hard to take it all in, and, to be honest, it can be

bit of a sensory overload. I was still holding onto bits of Thursday’s show

when I arrived at the entrance to the former

crematorium turned cultural space in the Wedding district on Saturday. The 19th century buildings are

stately, the grounds surrounded by the period architecture that makes up the most stately parts of Berlin, and deep

underground, in the ‘Betonhalle’, the performance space is a high-tech set up. Large video displays

on each of the walls live-casted concerts and video installations, all showing

different angles. (During one set I was wondering why someone seemed to

starting directly and unflinchingly at me, until I realized he was

concentrating on the screen to my left, while I was intent on the one to the

front).

The opening show was a live-cast from Johannesburg.

Bassist and composer Shane Cooper and the Dinaledi Chamber Ensemble performed

a suite of new music. The music was pleasant as it explored and layered

folk-like melodies with light electronics and poly-rhythmic ideas.

|

| Nate Wooley’s Columbia Icefield. (c) Cristina Marx/Photomusix |

drums opened the next set from trumpeter Nate Wooley and his Columbia Icefield

project. The mournful, charged, amplified breath blew a cold breeze across the

stage. It was musical dawn, and guitarist Ava Mendoza provided the first rays

of light breaking through the tonal darkness. Deep, thick

droning tones hovered in the background, emanating from Susan Alcorn’s pedal

steel guitar. As the music awoke, the textures came into sharp relief:

Wooley changing from a metallic rush of sound to a mournful melody, drummer

Ryan Sawyer adding additional texture, and Mendoza delivering aggressive

arpeggios and discordant tones.

where the Columbia River’s waters collide with the tumultuous Pacific ocean.

The tentatively titled tunes certainly projected this atmosphere. From the icy winds to the soaring grandeur. Plus, the ghosts

of western music are strongly bound with Alcorn’s instrument. While

her playing far transcends ‘country’, she brings something intangibly

‘western’ to the setting. The music is impressionistic and often slow moving,

but also at times explosive, it works its way between memory and feeling, and

leaves a long lingering impressions.My goal was to trace the physical breadth of the concert as much as possible with the time I had (I covered about 1/3 of the concerts, and 3/4 of the locations), so I left the

Betonhalle for the Kuppelhalle, after catching the first twenty minutes of the

riveting drummer/vocalist Maria Portugal’s set of explosive free-jazz and

Brazilian flavored music. At the Kuppelhalle, the smaller, cathedral-like

former mourning hall, Turkish vocalist Cansu Tanrıkulu performed with a trio

plus one. The trio, saxophonist Tobias Delius, bassist Greg Cohen, and the

plus one, guitarist Marc Ribot. How could I not be there? I would have surely

died from FOMO had I not been.

|

| Cansu Tanrıkulu Trio +1 (c) Cristina Marx/Photomusix |

Beneath projected video art featuring images of the vocalist,

emergency blankets, and CRT monitors, the trio + 1 wasted no time getting

started. Tanrıkulu’s otherworldly vocals sailed effortlessly through the

octaves and around Delius’ powerful lines. Throughout, Cohen was aflutter and

at first, Ribot – was he even plugged in? – scratched at his strings, but then

over Cohen’s unwavering rhythm, the guitarist starting building up a jazz

inflected solo that went from an acoustic whisper to splitting its pants. The

music, a freely improvised cocreation of the moment, was impulse and reaction.

It breathed naturally, unforced, and as precise as it was unexpected.

|

| Ahmed (c) Cristina Marx/Photomusix |

Ahmed, an ensemble, named after oudist and bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik,

comprised of British pianist Pat Thomas, French drummer Antonin Gerbal,

Berlin-based Swedish bassist Joel Grip, and British saxophonist Seymour Wright.

The group, which bases its music off motives composed by Abdul-Malik for his

Middle-Eastern/Jazz fusions, spent the better part of an hour locked in a

hypnotic and demanding groove. The music had the feel of something from

another time, Middle Eastern jazz noir, so to speak. Grip and Gerbal were a

relentless and powerful engine driving the music, while Wright blew

ceaselessly, twirling the themes around and around, making small incremental

changes and adding tension at every turn. Thomas sometimes struck the

extremities of the keyboards with his palms flat out, as percussive of an

action as one can do while still making music with the instrument. This

approach was interspersed with close dissonant tonal clusters that effectively

wound the music ever tighter. Often in improvised music the flow is to start

exploratory and searching until locking into something, these guys had it all

backwards, and it worked! They only backed off at the very end when Grip

seized the moment to quickly distill everything just played in a highly

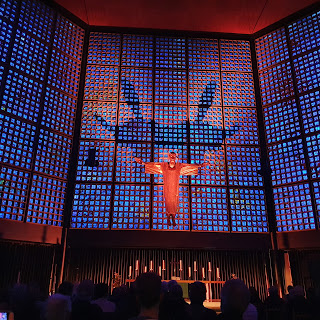

effective solo bass outro.Sunday at the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church

single concert on the last day at the other location for the festival, the

memorial church on Kurfürstendamm in Charlottenburg. The memorial church is an octagonal building comprised of a staggering 21,292 stained glass inlays. The

original church spire, heavily damaged in World War II, remains as a reminder

of the atrocities. Around the church grounds, there are barricades

everywhere – a reminder of the ever under construction city and unfortunately of the 2016

Christmas Market attack.

and traffic fences, we entered the church and picked a seat facing the large

Jesus sculpture and settled in for the solo organ piece from Norwegian

keyboardist Ståle Storløkken, the man at the heart of Elephant9 and

Supersilent, as well as a key member of Terje Rypdal’s groups from the past

decade or so. I had no idea what to expect, but what came next was

something that I actually had a hard time taking notes on as it unfolded.

|

| Ståle Storløkken. (c) Roland Owsnitzki / Berliner Festspiele |

listening event, as the organ itself was above the heads of the audience,

invisible. So, the mind wanders and at some point I wondered: could the music

itself work outside of the church itself? Could you sit at home and have this

experience, one where, left with just the music, and under the outstretched

arms of Jesus, indistinct memories and thoughts mix and travel through you in

their own ghostly vehicles? My thoughts were interrupted, however, when

Storløkken pulled out all of the stops and in an existentially threatening

moment, seemed to play all of the notes at once, jolting all back to the

now.I left a bit puzzled, and wonderfully so.

Watch it all here, available for a year:

https://www.arte.tv/de/videos/RC-020309/jazzfest-berlin/