By Paul Acquaro

In 2017, my wife and I visited Munich’s Haus der Kunst, an imposing concrete building set on the edge of the English Garden, and next to the Eisbachwelle, the mission to see the FMP exhibition. We did not have much time on the vacation, so we skipped documenta 14 in Kassel, even though it only happens every five years, making instead a beeline for Bavaria. We did make one stop by an acquaintance who worked in the music department of a store a short walk to the Haus der Kunst. He reported that he had taken to bringing his lunch to the museum to better absorb the exhibition. It made sense. There was a lot to see in one go. It turned out that the exhibit made its way to Berlin’s Akademie der Kunst in Tiergarten. This time, while on a different visit and due to a snowstorm cancelling flights at JFK, I was able to make repeat visits, however, it still felt like I had not taken it all in.

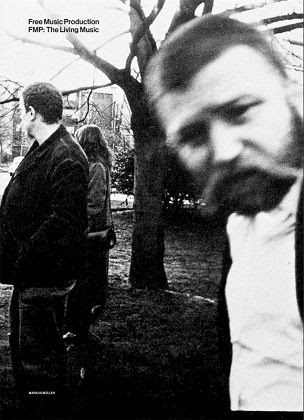

What was it about the exhibit that was so overwhelming? The walls of framed LP covers? The plethora of listening stations? The choice selection of Total Music Meetings and Workshop Freie Musik concerts projected on the white walls? Or perhaps the concert series that brought together (and back together again) an international cast of musicians who had helped make FMP a legend? (See FJB’s coverage of the exhibits and concerts here, and here). While it may be hard to pinpoint exactly what, a thread that connected it all was the careful curation of Markus Müller, the author of FMP: The Living Music, a hefty tome that serves as both the ultimate museum catalog for the exhibitions and a must have chronical of the work and history of FMP for anyone interested in the development of free jazz and avant-garde in Europe and beyond.

The near 400-page coffee table sized book is rich with reproductions of the documents detailing FMPs contracts, organizational structures, yearly statements, and more. There are the LP and CD covers and event posters, in which the visual work of Peter Brötzmann and Jost Gebers (both with a background in graphic design) resulted a highly identifiable aesthetic. Also bountiful is the iconic black and white photography of Dagmar Gebers and photography of the events in Munich and Berlin from Cristina Marx, Maximilliam Gueter, and Uwe Weber. Images of the main players like Peter Kowald, Brötzmann, Alexander von Schlippenbach, Hans Reichel, Sven-Åke Johansson, Cecil Taylor, Brötzmann and Gebers, mix with the recent ones of Brötzmann, Schlippenbach, Johannson, William Parker, Hamid Drake, Kelji Heino, Toshinori Kondo and many more (listing all the names is a problematic task!). In a sense, the imagery is worth the price of the book alone, a visual history of FMP, but Mueller’s text adds so much rich explanation and context that the book’s real value far outstrips its (actually quite decent) retail cost.

Müller’s passion for FMP, from the music to the personalities to the contours of how its history fits with the history of cold war Germany, comes through clearly in the text. The structure is well conceived and in a sense, follows the sections of the museum exhibitions (a download of the program Munich is available as of this writing, here). The sections cover a general introduction to FMP to a detailed history of the now highly collectible LPs (average price for an original FMP is about 50 Euros, even the CDs go for 20 Euros for elusive new old stock); the relationship that FMP made with East German’s who were so close and yet so far just across a wall (the Bauer brothers, Gunter “Baby” Sommers, Ernst-Ludwig Petrowsky, and Amiga Records, all play a prominent role here); the role of woman in a predominately male-dominated scene; and of course the later relationship with Cecil Taylor which resulted in the coveted “Cecil Taylor in Berlin ’88” which can be scored for a mere 700 to 800 Euros (or $125 digital with the book separately available). See the FJB review of the digital release here.

Müller’s text starts at the beginning. FMP began as a protest of the status-quo when Brötzmann did not agree to the Berliner Jazztage’s (now Jazzfest Berlin) request that his group wear black business suits. Gebers and Brötzmann instead organized the first Total Music Meeting. Staged opposite the festival in 1968 at the nearby Quartier von Quasimodo, the sweaty set of concerts featured the Peter Brötzmann Group, the Donata Höffer Group (with Gebers who was a bass player at the time), The Globe Unity Orchestra, The Spontaneous Music Ensemble, the Gunter Hampel’s Time is Now, Manfred Schoof Quintet, and pulled in some after-hours players from the festival. Photos show Pharoah Sanders and Sonny Sharrock kicking it up, and a young John McLaughlin with Hampel. Following this, things took off for Gebers and Brötzmann, connecting with the self-empowerment Zeitgeist, they began to issue recordings, the first being European Echoes from trumpeter Manfred Schoof and organizing further events. The tale of the first Workshop Frei (then entitled “Three Days of Living Music and Minimal Art”) at the Akademie der Kunst in West Berlin is told a few different times, as sort of an early inflection point. The concert, which featured Schlippenbach and Alexis Korner playing amongst art, ended prematurely due to the artwork being vandalized by excited concert goers. Gebers had thought it meant the end of the relationship between the nascent FMP and the generous Akademie der Kunst (AdK), but it turned out he was wrong and the institute became a fixture of location and funding for the event for many years. The book dedicates a section to the Workshop Freie Musik and the special edition box set that was originally released in 1978 (FOR EXAMPLE: Workshop Freie Musik 1969-1978, downloadable here with PDF of the booklet)

Where Müller’s text really shines is in going beyond the myths and history and gathering the recollections and feelings of the people involved. An important aspect of FMP is that its reputation and influence far outstrip the funding and resources it had, and his interviews and quotes capture the energy and sweat that went into keeping it going. In fact, there are three distinct moments of organization for FMP, beginning with the duo of Gebers and Brötzmann, to the few years in the early 1970s when it became a collective with Schlippenbach, Kowald, Gebers, and Detlef Schoenberg, to when it settled with Gebers in charge in 1976 and he, along with his wife Dagmar and a single employee, Dieter Hahne, rode the tides and produced the recordings, concerts, and festivals that make up the bulk of FMP’s legacy, all the while the Josts putting their own money from their day jobs into the endeavor. Key quotes from Hahne, Dagmar Gebers, Brötzmann and others attest to the focus and tireless dedication of Gebers to the organization.

The impact of cultural and political movements and realities also both shaped and supported FMP. Born in the divided city of Berlin and (first) wrapping up a decade after the Berlin Wall came down, FMP benefitted from the cultural support that was available, and in turn gave back much more, to Berlin, Germany and beyond. The chapter about the relationship with East Germany is fascinating. Gebers established relationships with the state-run Amiga recording company and made connections with East German musicians, offering chances for them to play in the West and sharing publishing of recordings with Amiga. There are anecdotes about East German musicians defecting after a show where they had been given permission to play in the West, and the worry that Gebers had (but never materialized!) about it. Out of this relationship came the double album SNAPSHOT/JAZZ NOW – JAZZ AUS DER DDR a double LP showcasing the music of players like Petrowsky, Conrad and Johannes Bauer, Manfred Schulze, Ulrich Gumpert, and others. This one is available for download along with the excellent booklet. Also check out one of my favorites, ‘Round About Mittweida by the Conrad Bauer Quartett (later Doppelmoppel).

Müller also addresses the importance of woman in FMP, as the free music scene was as male-dominated as most avant-garde art movements at the time. A chapter highlights the various collaborations with women musicians starting with singer Maggie Nichols and pianist/singer Donata Höffer at the 1968 Total Music Meeting, to the many performances and recordings with pianist Irene Schweizer, and eventually the Feminist Improvising Group (FIG) in 1979 and which later became the European Women’s Improvising Group (starting in 1983). Interestingly, it seems that performances by FIG drew a lot of criticism, though it treaded on similar grounds to music and slap-stick humor that other male groups drew praise for doing. A later arrival to the FMP fold was bassist Joëlle Léandre, who can be heard in collaboration with clarinetist/accordionist Rüdiger Carl on one of FMP’s highly enjoyable CD releases Blue Goo Park.

It would be an unforgiveable oversight not to mention Cecil Taylor’s 13-CD Boxset again. It is simply that famous. Mueller quotes Dagmar Gebers being delightfully surprised by how the boxset’s reputation had traveled world-wide, while Gebers talks about the frustrations, and ultimately the success, of working with Taylor. The pianist recorded, aside from the box set that documented his month-long residency in Berlin, fourteen other CDs for FMP, all available on Bandcamp, like Nailed with Evan Parker, Barry Guy and Tony Oxley, and two from the Feel Trio with William Parker and Tony Oxley. FMP: The Living Music also features an essay by music critic Diedrich Diederichsen on the technical development and context of Taylor’s work in Europe and offers a somewhat behind the scenes look into how his music made in Berlin came together. There are also a number of Dagmar Geber’s photos chronicling the process.

What Müller accomplishes wonderfully with this book is not only an encapsulation of the exhibitions in 2017 and 2018, but more so, delivers a fleshed-out reflection on the development of a scrappy DIY endeavor from West Berlin whose festivals, recordings, and general aesthetics are still being felt. For example, there are still efforts to keeping the music alive, such as Trost Records in Vienna re-releasing FMP albums on its Cien Fuegos label; Corbett vs Dempsey in Chicago’s high quality CD re-releases; and Gebers himself has been scouring his archives for digital releases. Additionally, current festivals such as the A L’arme! Festival in Berlin, it has been argued, are keeping the traditions of the TMM alive, while adapting to the times.

FMP: The Living Music is an impressive volume. Reading it was a pleasure – though practically it was not always the most comfortable book to try to hold and read. I came to think of it as a page turner whose pages were hard to turn, but once you reconcile the physicality, be prepared for a thoughtful and thorough digestion of FMP and the people who made it happen.

– 39 Euro, direct from Trost and other book dealers.

– Available in the US through Corbett vs Dempsey.