By Eyal Hareuveni, Sammy Stein, Gary Chapin, Tom Burris, and Paul Acquaro

In 2021, the prolific tenor sax player celebrated his 60th birthday with a major project, a nine-volume box, Brass And Ivory Tales (Fundacja Sluchaj, 2021), seven years in the making, and pairing Perelman with nine like-minded pianists. The improvised dialogues were often the first formal meeting between the Perelman and the pianists and the instant and rapidly evolving synergy was fresh and rewarding. Perelman focuses on camaraderie in his creative process and excels in maintaining his individuality while matching the idiosyncratic style of each of his partners.

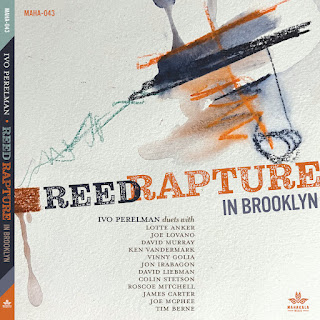

In 2022 Perelman had released another magnum opus, the 12-volume Reed Raptures in Brooklyn, in which he meets and improvises this time with 12 reeds players, most of them for the first time. In fact, Perelman seems to be enjoying this approach as has plans to release another box set that documents one-on-one recordings with guitarists. Reed Raptures in Brooklyn is a celebration of the sax (ten different ones) and clarinets (three different ones) family, recorded over six months in 2021. These meetings cover a kaleidoscopic range of sound and offer another testament to Perelman’s dynamic musical evolution.

With Joe Lovano:

The fourteen tracks of Perelman and Joe Lovano demonstrate the different styles of each player, here succeeding in developing a dialogue thatfeatures sharp, shared phrasing and often intense, creatively interwoven episodes. Lovano demonstrates his versatility, egged on and encouraged by Perelman’s delirious and, at times, profoundly evocative playing. Creative interludes flow from blues-infused riffs, walking-paced marches, and dramatic, high-reaching held notes making for tone poems that interweave,

switch the emphasis, and add color to phrasing, which only two musicians intensely listening and responding to each other can produce. Contrasts between the atmosphere on different tracks, from slower, whimsical melodic exchanges to dramatic contrasts, demonstrate that this pairing elevates

both musicians’ playing to new heights. (Sammy Stein)

With Tim Berne:

Sometimes it feels like each duet creates a new space, with new rules, and new physical laws; sometimes it feels like Ivo is entering the “world” of his interlocutor. Tim Berne’s compositions are famed and beloved, and his free improv is equally admired (see his Paraphrase sets) and equally a product of his unique voice. This set of five-edged conversations (arguments? contretemps?) sees Berne spending a lot of time in the jaggedy upper extensions of the saxophone—though his tendency to go from there to a low, low contemplative thought is kind of heartbreaking—and Ivo is happy to join him there. I’m sure others will have commented on the uncanny ability of Perelman and friends to reflect back at other (through imperfect mirrors) motifs, themes, moods. They whip and wend like birds in a murmuration. A saxophone dance with no “primas.” (Gary Chapin)

With David Murray:

David Murray plays exclusively the bass clarinet on one channel, while Perelman is on the other. Murray has one of the best bass clarinet voices ever, and it sometimes takes a spare setting like this to appreciate. From the first few seconds, I was loving just the sound of his horn. He’s also got one of the better dry senses of humor in our music. There’s almost this sense that Murray is laying a path, and Perelman is happy to play Alice to Murray’s rabbit. They chase each other around various settings, with wild outcries and celebratory yawps. They are having a great time on this one. I smiled a lot. (Gary Chapin)

With Lotte Anker:

Danish alto and soprano sax player Lotte Anker is the only female and non-American sax player here, but although this is her first meeting with Perelman both share similar aesthetics. Both are fearless and imaginative, kind of stream-of-consciousness, free improvisers who often frame their improvisations into instant, loose compositions. The opening, 90 seconds of “Eight” show how Anker and Perelman can crystalize their camaraderie into a touching ballad. The following pieces are much longer pieces are also much more fiery and energetic, but so is the rapport of Anker and Perelman, both often complement each other’s ideas, interweave their voices and explore a playful and harmonious balance between Perleman’s higher ranges of the tenor sax and Anker’s lower ranges of her alto and soprano. Anker often

adds lyrical, melodic veins or hauntingly abstract musings into the intense, energetic dialogues, as on “Six” or “Three”, taking this meeting into deeper spiritual regions. (Eyal Hareuveni)

With Ken Vandermark:

Ken Vandermark brought his clarinet to his first meeting with Perelman. They play a set of twelve brief pieces, exploring an idea with short but dense, precisely matching phrases, exhausting their options and with no attachment moving to the next one. These eloquent, balanced improvisations swing between spirited, urgent discourse and lyrical and compassionate musings, almost chamber ones (check “Thirteen”). Hrayr Attarian, who wrote the insightful liner notes to this box set, wrote that Vandermark and

Perelman’s dynamics are “musical equivalents of a cross between freestyle poetry and flash fiction”. You may also think about this meeting as a heated and vibrant conversation between kindred souls who have a lot to share and unburden in a short while, with extended breathing techniques and an acrobatic demonstration of circular phrasing, squawks with honks, even if Vandermark and Perelman often have dissonant perspectives. Given their immediate and deep rapport, Vandermark and Perelman just began to explore the potential of such collaboration. (Eyal Hareuveni)

With Roscoe Mitchell:

Roscoe Mitchell also sticks exclusively to the low end, playing bass sax. This is the only recording that Perelman left Brooklyn to record, and we should be glad he did. It’s a grand phenomenon for me that, as I plow through my 50s, to be reminded of things that I’ve forgotten. Not forgotten exactly. I hadn’t forgotten how good Roscoe Mitchell could be, but I had forgotten what it felt like to get a first listen to him being one of the most amazing creative musicians of all time. Yeah, I know what I said. These

three tracks are a joy. Roscoe plays the bass track with a strategy. His game—a long game—is made of low pitches dropped at even intervals, at a not raucous pace. Perelman skitters over him, and you can hear, sometimes, that Perelman is trying to tempt Mitchell to flight, but Roscoe is not having

any. (disclaimer: I don’t know for a fact that this is what either were thinking. It’s an impression.) And his persistence—in comedy they call it committing to the bit—his ongoing, breath paced desultory rhythmic

minimalism becomes something transformational. A slow process over time that you don’t always notice because Perelman is doing some very cool stuff above. But when Roscoe, about halfway through, shifts to more melodic phrases, the satisfaction via contrast is extraordinary. An amazing set. (Gary Chapin)

With James Carter:

The Carter-Perelman pairing, with Carter on baritone, is ebullient and dynamic. Carter brings his range of styles to the fore, and the joy of this pairing is palpable as they come together, drift apart and then slam with such force the air trembles. Carter is controlled, Perelman more spontaneous, but equally, he listens and changes tack several times to align with Carter’s dynamic, beautiful playing style. Carter’s

blaring baritone is matched by Perelman’s equally fiery explosions and tonal responses. There are fleeting echoes of classical compositions intertwined with immense improvised sections throughout which the pair maintain an intimate, witty conversation infused with delight. In a few places, Carter lets rip some rock-infused blasts, which Perelman responds to by allowing Carter to play solo before dropping his reply into the pattern. This is a remarkable and provocative pairing, demonstrating Perelman’s versatility in adapting his playing to allow a fellow musician to bask in the delight of improvisation and doing so himself. From diverse streams, the pair come together in harmony at times before veering off again, each on his own path but constantly surging back to the other. The music flows effortlessly from two brilliant masters. (Sammy Stein)

With Jon Irabagon:

Perelman’s duet with Jon Irabagon never had a chance of being a run-of-the-mill affair, that

simply is not a choice with these two innovative and energetic musicians. The opener, ‘Six,’ begins with a squall of notes followed by the sounds of giddy, avuncular baby aliens. The chattering sounds accompany Perelman’s nascent melodic lines. Three minutes into the piece, the two have gone

through a set of tandem legato melodies, followed by a stretch where Perelman presses against Irabagon’s storm of extended sopranino saxophone techniques. Towards the end of the track, they

seem to have found a sort of tune with piercing counterpoint from the tiny sopranino saxophone. On the following track, ‘Seven,’ the two carry on in a deeply syncopated, ping-ponging manner, reaching unusual

levels of cohesion – both melodically and in sonic terror. Track 5, entitled “Three,” is a jittery piece, made up of shards of contrasting sounds, but comes together to end in an intense burst of intertwining musical purpose. Throughout their meeting, the moments of unfettered sound making is equal to the melodic ideas that they share. (Paul Acquaro)

With Joe McPhee:

Let’s just get this out of the way. Both Ivo Perelman and Joe McPhee are absolute masters of improvisation and the instant compositions on this disc only serve to solidify their positions. The most obvious mode of operation here is that McPhee riffs in the lower registers of the tenor while

Perelman flies around up in the ether. But that’s merely where most of the pieces begin or “go home.” Our heroes also wind around each other in the same register and pop into the stratosphere with similar punch and vigor, making it challenging at times to tell who is going what. This collaboration bears beautiful and often hypnotic results, as on “Five” or considers the magic weaving that conjures up the mysterious feel of duduk player, Djivan Gasparyan on “Two”. But at turns their conversations can

become weepy and dark, or they can ascend into an Ayler brothers’ style of rapid jabs and punctuation. My favorite of the bunch is “Three,” where Joe howls and brays at the stars that Ivo is punching into the night sky before both tenors begin the speedy process of connecting them with musical lines. McPhee has an epiphany of some sort that prompts him to begin speaking in tongues. When Ivo responds, it’s nothing less than overtones of the barnyard and several stalls require cleaning. (Tom Burris)

With Colin Stetson:

Montreal-based multi-instrumentalist Colin Stetson brings to his first meeting with Perelman the contrabass saxophone. Perelman and Stetson’s duets attempt to find common, resonating ground between the higher register of Perelman’s singing tenor sax, which can be associated with his recent

study of bel canto opera, and the vibrating, deep-toned growl of Stetson’s contrabass saxophone, including his extended breathing techniques that add percussive and otherworldly abstract touches. These patient, slow-cooking duets stress, again, Perelman’s uncanny ability to create spontaneous and

stimulating synergy. These free improvised pieces sound like introspective and contemplative, deep meditations on the contrasting, sometimes dissonant and quite intriguing sonic palettes of the two horns playing together, but rarely reach turbulent, cathartic climaxes. (Eyal Hareuveni)

With Vinny Golia:

Playful, challenging, but accessible, it’s not hard to find your place within the intertwining lines of these two woodwind masters. Golia, a master of a seemingly endless array of woodwinds, here sticks to clarinet,

the basset horn – a slightly darker toned mid-sized clarinet – and the smallest of the saxes, the soprillo, trades lines deftly with Perelman in this alluring meet-up. The opening track, ‘Seven,’ begins with the lightly aching sound of Perleman alone, delivering a seamless stream of notes. A hint of a melody creeps

in at some moments, and then Golia comes in on the clarinet, his sound a bit woodier than Perelman’s. The two slowly build up their conversation, reacting to each other’s musical intentions telepathically. Track

two, entitled ‘Two,’ begins again with Perelman alone, but his arching lines are soon traced by Golia, at times the two seem to stretch their notes out over vast musical spaces, both complementing and competing with each other. Track ‘Six’ begins with Golia solo, his clarinet a buzz of arpeggiated runs. Perelman reacts with his own vibrating melodies that sometimes seem to spiral away from his horn into curlicues of air. The track ends with a sonorous tone from Golia as he then recaps his kinetic introduction. The interactions are rich and rewarding throughout this entire encounter. (Paul Acquaro)

With Dave Liebman:

The Perelman-Liebman tracks are immersive, and Liebman is given rein to bring his expansive range of style and expression to this series of duets. The silences are as important as the playing in some parts, and Perelman here shows his innate ability to tune towards another musician in exemplary lead or reaction, depending on the nuance of the piece. Each dialogue explores a different part of the unifying language of the music, with some tracks feeling like two or three as the atmosphere switches from sublime to dramatic dynamism. Liebman, at times, takes a suggestion from Perelman and works his emotive response, which intuitively, Perelman then re-takes and places his voice on it. There are moments when Perelman briefly sets up a blues/rock theme under Liebman’s whimsical top line, the line vanishing when the lead switches back to Perelman. At other times, the pair swap short, sharp riffs, reflecting and changing them, often ending as Perelman screams down the scale. These swapped themes echo throughout the tracks, creating a series of interlinked yet distinct conversations. Immersive and completely spell-binding. (Sammy Stein)