By Paul Acquaro

set of dates, a long weekend in one place, a series of shows starting

sometime in the evening of each date. A variation can be overlapping

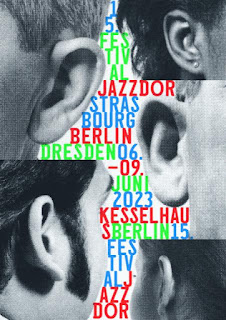

events at multiple locations – something that adds a bit of tension for the festival goer. The Jazzdor organization, however, has chosen the other variable for their festival, space. The festival, which

has been happening since 1986 in Strasbourg, France, and since 2007 in

Berlin, has in recent years been slowly expanding further across the continent, first

to Dresden and now also to Budapest. At the festival’s heart is the

collaboration of French and German musicians, but it also casts a wider net as it offers the

engaged listener a journey of both discovery and creation.

I would attend a night or two. Perhaps drop in to see a known (to me) musician

or group, but not taking in the entirety of the event. This year was different, I went diligently

every night to the Kulturbrauerei located in Berlin’s dynamic Prenzlauer Berg

neighborhood and consciously did not allow any expectations from the names and

descriptions in the program to proceed me. This was the

perfect approach. There was hardly an act that did not hit some of the

right buttons and if the number of CDs one picks up at the merch table is a

valid KPI for judging the success of a festival, then for at least one

attendee, the festival was a smashing success. Allow me to explain.

Tuesday, June 6th

|

| O.U.R.S. Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

Clément Janinet’s O.U.R.S (short for the enigmatic ‘Ornette Under the

Repetitive Sky’), a quartet with Janinet on violin, Hugues Mayot on woodwinds,

Joachim Florent on double bass and Emmanuel Scarpa on drums

and vibraphone, that combines concepts from Ornette Coleman’s music with

the repetitive minimalist concepts of Steve Reich. The result is a slowly

unfolding, churning, legato swell of music that borrows elements from

post-rock as well as Coleman’s suspended moods (a la ‘Lonely Women’), building to

dense and tense peaks. Instrument changes added new colors, such as the

electric mandolin replacing the violin, or vibraphone instead of

drums. On their final extended piece dedicated to Alice Coltrane, the band worked

with uneasy grooves and long exploratory passages to come to the journey’s

end. It was the type of set that leaves you feeling like you’ve landed elsewhere at

the end – in my case, at the merch table.

|

| Christophe Monniot’s Six Migrant Pieces. Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

of the Kulturbrauerei – a converted 19th century brewery complex – is quite canvernous. I had enjoyed the previous set from a balcony in the rear of the

rectangular hall but after my visit to the merch table, I had squirmed up to

the front row to gain a new perspective. After a 15-minute or so pause,

the premier of saxophonist Christophe Monniot’s

Six Migrant Pieces began. First as quintet, pianist Jozef Dumoulin

started out with a slightly dissonant intro followed by the entru of Bruno Chevillon’s

bass and Franck Vailant’s drums. Over a now forceful and driving pulse,

trumpeter Aymeric Avice and saxophonist and composer Christophe Monniot

delivered an urgent melody and then got quickly into heated solo exchanges. The

music, based on ideas of migrations of people and culture, was captured in a

modern jazz rock sound. The second tune welcomed fusion guitarist Nguyên Lê to the stage. His playing began with legato tones from

his electric guitar, then to the delight of the guitar lovers out there, Lê brought the energy to a high point with his searing tone and fleet fingerings. Avice, too,

was a true stand out during the set, and in a subsequent apperances with his

lyrical, biting playing. The ease in which the

sextet moved in and out of the songs evolving passages had roots in Weather

Reports early style (which was empirically evidenced by a song being dedicated

to Wayne Shorter), but one shaped by Minniot’s modern melodic

sensibilities and the group’s strong musical personalities.

Wednesday, June 7

|

| Didier Ithursarry and Elodie Pasquier. Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

The three events on the second day of the festival began with a duo with

a more folk or classical instrumentation: Didier Ithursarry on

accordion and Elodie Pasquier on Bb and bass clarinet. Throughout the

set, the duo’s warm, reedy timbers flowed and eddied around each other in a

constant stream. The accordions gentle chords and harmonic stops provided a

sumptuous background for the clarinet’s sometimes dissonant melodies. When

Pasquir switched to bass clarinet, she introduced a gulping groove and with

Ithusarry’s turn to deliver the melodic component, generated a close-knit

dense energy. The musical pieces conveyed an often romantic, but also

sometimes starkly modern classical approach with some blue notes interspersed.

The duo had a strong, unique sound and was a expectation setter for the night.

plays traditional instruments with wild creativity. Minimalist

grooves emanate from unusual techniques – for example Lete placing small

boxes on his electric bass, which he lays flat on his lap, and then plays like

small hand drums, creating a thumping pulsation which Aymeric Avice, returning

on trumpet(s) and drummer Toma Gouband react to and shape in thier own ways.

Like, Gouband using lettuce, bananas and plants picked from the sidewalk as

drum sticks (yes, his playing is very organic) and/or Avice using two trumpets

at once. The kinetic bass lines and often mournfully lyrical statements from the trumpet kept the experimentalism from stripping away the

musical aspects, allowing the audience to get some grip on the music. The set

was something completely unexpected, and one of those events that leaves you

slightly bewildered but utterly changed at the end. The trio has also just

released a recording on Jazzdor’s own imprint which is as beguiling as the

concert.

|

| Sylvain Rifflet’s Rebellions. Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

The set length is generous for a festival, each one stretching at least an

hour. Thus, the evening ended late with saxophonist

Sylvain Rifflet’s quartet featuring the irrepressible

Jon Irabagon also on saxophone and Sebastien Boisseau on bass and

Christophe Lavergne on drums. Organized around a set of famous speeches expressing rebellion at power structures and status quo, the group translated

the intensity of the words into intensity of music, creating a synergy that

propelled each other. Pulling on a diverse set of speeches, from the sonorous

voice and erudite words of civil rights activist Paul Robeson, to the youthful

and incredulous modern day speeches of Greta Thurnberg and Emma Gonzalez

speaking out against modern afflictions of climate change and gun control, to

the French minister Andre Malraux, who eulogized WWII resistance leader Jean

Moulin, among others, provided a source of inspiration. The musicians played

along with the speakers’ voices, under their projected images, at first

tracing the contours and cadences of their voices and then spiraling out in

thier own directions. The two saxophonists played off each other, sometimes

simultaneously, delivering Rifflet’s empathetic melodies and their often

fierce solo turns. It was a powerful show and, of course, always a pleasure to

hear Irabagon letting loose. Their recording on BMC Records features Jim Black

on drums, but otherwise is a faithful representation of what the group brought

to the Jazdoor stage.

Thursday, June 7

|

| Dumoulin, Malaby, Ber. Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

Adding to the intercultural mix of the

festival, American saxophonist

Tony Malaby, along with Belgian drummer Samuel Ber and

keyboardist Jozef Dumoulin, who first played together at a bar in Brussels

in 2015, kicked off the evening with a hushed performance of beautifully

modulated analog synthesizers and reserved acoustics. The music grew slowly,

bound up in tension of potential. Malaby can be a very powerful

musician, pushing his saxophone to extremes, but he reserved that power for

choice moments when Ber’s precise drumming and Dumoulin vintage, textural

tones hit certain inflection points. It was hard to anticipate when, but when

they did, the music grabbed you. In between, they floated, the suspense

building, ebbing and flowing leaving the audience warmed up and ready for more.

Bonnet/Raulin/Ladd/Chevillon/Rainey – an unheard combination,

even – almost – to the musicians themselves, who had only a quick rehearsal the day prior.

Conceived of by the festival, organizer Phillipe Ochem explained that the core

of the group, guitarist Richard Bonnet and pianist Francois Raulin, started with a series of compositions written with the haiku poetry form in mind and

then fused it with the lyrical prowess of Paris-based American spoken word

artist and rapper Mike Ladd, along with the rhythmic force of American drummer

Tom Rainey and French bassist Bruno Chevillon. A daring venture and one

resulting in an absolute success. Sure, there were some parts that could

probably be tightened up, but the excitement from the stage was palpable and

the music flowed generously. Ladd’s improvised lyrics contained childhood memories of Boston, mentions of Rikers, bikers,

Nazi prison guards and much more, all spilling out rapidly over lurching rhythms

and Bonnet’s infectious harmolodic guitar work. When Ladd stepped back, the

group balanced melodic improvisation with energetic free jazz. Ladd’s heart-felt

tribute to a dying friend was a touching piece worked with an austere bass

line and leading to lovely tone poem like accompaniment. Too new of a band for

a recording, but I’m keeping my eye/ear on it.

|

| Musina Ebobissé’s 5TET. Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

Olga Amelchenko on alto saxophone, Povel Widestrand on piano, Igor

Spalatti on double bass and Moritz Baumgärtner on drums. The concert was

also a release show for their newest CD Engrams on the Jazzdor label. With

members from France, Russia, Sweden, Italy and Germany, the pan-European

collective delivered sophisticated modern jazz with strong compositional

elements and hints of free-playing. The interplay between Ebobissé and

Amelchenko seems to form the center of the sound, with the alto often

shadowing and reinforcing the tenor lines, but then breaking away and both

playing impassioned solos. Their highly crafted music had a certain “ECM-vibe”

to it, cool, at first, building, inner rhythms and subtle energy shifts

helping bring each subsequent song a bit more intensity. An invisible string

connected each of the musicians, who all reacted subtly to the others movements. Widestrand’s piano playing was often quick,

melodies appearing between the comping, while Baumgarten’s dynamic tensions and

Spalatti’s swooping bass work gave the saxophonists plenty of support and

space, often helping to push the whole group to reach densely constructed

musical peaks.

Friday, June 8th

|

| Takase, Sclavis, Courtois. Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

The final night of the festival, before the enterprise got on the road to

Dresden for a further weekend of concerts at the venerable Jazz-Tonne club,

began with Berlin’s own Aki Takase along with clarinetist

Louis Sclavis and cellist Vincet Courtois. Starting with a

percussive and decisive motif with the piano and cello hitting downbeats in

tandem, Sclavis, on Bb clarinet, quickly ran up and down a scale. Then, just a

suddenly as it had begun, it began again. Quick hits and then the cello and

clarinet leaping into an animated duet. Then pivoting to Takase, Courtois

utilising a buzzing effect with his strings, engaged in another feisty

exchange with equally energetic pianist. A strong sense of classical music permeated the music, informing the improvisation as sweeping melodic

blocks collided and reformed on impact. Their next tune featured a long solo

passage from Sclavis that ranged from the romantic to the blues, followed by a

stretch from Takase that swung from exuberant to defiant and back. Later,

Sclavis, switching to bass clarinet, took the instrument to its expressive

extremes as Courtois played the cello as if it were both a bass and guitar

simultaneously. Then, the extended techniques kicked in with Takase bouncing

ping-pong balls off the piano’s inner strings, and as one would, for comic

effect, secretly hope for, a ball bounced into the bell Sclavis’ horn. A

gently humorous, but more so, an extremely engaged, opening set.

|

| Naïssam Jalal’s Healing Rituals.Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

premiere, and Jalal, an avuncular and warm presence on the stage, turned at one point to

the audience and explained that the previous night she had played in France to an

exuberant and whooping crowd. A bit bewildered by the quiet audience in the

Kesselhaus, she asked if they liked what they were hearing – to which

exuberant applause and whooping ensued and a cross-cultural barrier had been

broken. The music, a unique blend of Arabic folk music and western Jazz,

created a beguiling synthesis of the various influences. Jalal switched

effortless from flute to a wordless signing approach seamlessly, and the

interlocking virtuosic playing of Clément Petit’s cello and Claude

Tchamitchian’s double bass was often mesmerizing. Zaza Desiderio’s percussion

underscored all of the music, from gentle, supportive hand drumming to

pulsating stick work. Gentle introductions led to rhythmic journeys which

Jalal navigated with warm persuasiveness. Premiering a new recording and set

of music, Healing Ritual, Jalal’s new compositions are in reference to

rituals around the body, nature, and play. The music from the stage did

envelop the audience with its rhythmic flow and hypnotic, and sometimes

insistent, melodies. Jalal herself was a centered and calm presence amidst the

swirling energy of music, engaging the audience through authentic banter and

her addictive multi-cultural musical melange.

|

| Daniel Erdmann 6TET: Couple Therapy. Photo by Ulla C. Binder |

in France – saxophonist Daniel Erdmann. A frequent collaborator of Aki

Takase, tonight Erdmann led a sextet that was a creation for the festival and

featured the impressive line up of Erdmann on tenor saxophone, Hélène Duret on

Bb and bass clarinet, Théo Ceccaldi on violin, Vincent Courtois on cello,

Robert Lucaciu on double bass and Eva Klesse drums. The name of the

group, “Couples Therapy,” was conceptually a play on the relationship between

France and Germany, the two driving forces of the European Union, which speaks

to the Jazzdor festival’s central concept.

boil, Erdmann delivering short melodic snippets, then connecting and

elongating them until they became a groove-based modern jazz melody.

Through mounting intensity, the group generated a collective sound, and

Klesse, with a formidable expression on her face, gave the music a

real push. The next tune featured Duret’s clarinet work and also set a bit of

underlying pattern to the music, for a lack of better phrase, a “wobbly jazz”

in which the locus of control seemed a bit uncertain — perhaps

linked with the therapy concept. Both string instruments had star moments as

well, Courtois with classical leaning passages played with a great deal of emotion and longing, with melting voice leadings and deadly precise staccato phrases, and

Ceccaldi with an intense, rock-like violin solo that brought the set to its musical climax. Erdmann, while joining in

on the heads of the tunes and delivering several strong solos, often stood towards the back, a towering presence,

seemingly quite pleased, observing his musical creation.

projects, and of course an evolving assortment of goodies at the merch table,

it could be a bit overwhelming. However, the generous set lengths, the breaks

between them, and the generally relaxed atmosphere of the event helped it work

and more importantly Jazzdor’s curatorial concept provided just enough

structure to encourage each act to bring a high level of craft and

individuality to the stage. The end result is that I left simply as a

better listener than when I started. I’m also still unwrapping those CDs and

popping them into the player.