The AACM retrospective week begins with our highly subjective, entirely personal, and completely non-representative list of albums plucked from our own collections to represent what the recordings of the AACM and it’s musicians have meant to us as enthusiasts of the music. Today, the years between 1965 – 1974.

By Colin Green, Martin Schray, Matthew Grigg, Paul Acquaro, Stef Gijssels

Muhal Richard Abrams – Levels and Degrees of Light (1968)

As mentioned in the introduction, the AACM grew out of Abrams’ Experimental Band, a workshop that never performed in public in which he encouraged musicians to explore not just contemporary developments in jazz, but classical music and non-western traditions. From this, there emerged a focus on ensemble sound – texture and counterpoint rather than soloist led virtuosity – forms dictated by motifs, scales and timbres, and the use of instruments and sonorities unfamiliar to jazz. “I try and incorporate everything I hear,” Abrams said later, “I really try and transcend any style”.

As the name of the title piece suggests, this is music of subtle gradations. It’s scored for vibraphone and cymbal – tempoless and shimmering textures over which float Penelope Taylor’s wordless soprano followed by Abrams’ clarinet. There’s a change of pace in My Thoughts are My Future – Now and Forever. Abrams’ piano provides a toccata-like introduction, whose momentum is continued by solos from the horns and bass, which play with the tiny motif – barely a tune – which forms the melodic material of the piece. It concludes with Taylor’s soaring soprano and vibes lifting the music into the stratosphere.

After a short poem, the opening and closing of The Bird Song consists of overlapping arpeggios and extended bowing techniques from Leroy Jenkins on violin and two double basses, together with a bird whistle and cymbals, producing a microtonal aviary: a texture surely inspired by the works of Penderecki and Ligeti. Between, the “jazz band” plays at full pelt in a dense thicket of sound. As with the sections that frame it, this is music with no foreground or background, only surface.

From our current perspective, parts of the early AACM albums might seem a little dry and predictable in their attempts at cross-pollination – there’s still a touch of the workshop about them – but we should recognise that these musicians were to a large extent walking into empty space and areas that have proven to be vaster than anyone could ever have thought. For that, we owe them a debt. (CG)

Roscoe Mitchell – Sound (1966)

Generally regarded as the first AACM album, recorded in August 1966 – the year before Levels – it planted seeds that were to prove lasting and fruitful.

Mitchell (alto saxophone, clarinet, recorder) had previously played in an Ornette Coleman style quartet (recordings from 1965 were unearthed recently: Before There Was Sound (Nessa Records, 2011)) and although he’d moved on to other things, Coleman’s music still remained important. Mitchell’s Ornette is topped and tailed with a typical fast-slow blues tune. Between, there’s what superficially resembles the spontaneous energy music of New York’s “new thing”, but it’s actually more concerned with instrumental character and contrast than self-expression. The fact that the alternate take on the CD reissue, recorded a few weeks earlier, is very similar and of almost identical duration suggests that more planning went into the piece than at first appears.

One Little Suite sounds cute, but it refuses to behave. It starts with a succession of short, disparate tunes each scored very differently, much like a normal suite: hometown blues on harmonica and recorder, a bebop tune on trumpet, a snatch of a woodwind theme, and a parade day march. There’s then a series of jump cuts, the tunes interrupt each other, vie for attention, and the piece dissolves into a tantrum: an anarchic free for all where you can still hear the original fragments, strewn in all directions. The nearest equivalent I can think of is Carl Stalling’s music for the Looney Tunes cartoons, years before John Zorn started to make whole albums this way.

Perhaps the most remarkable pieces are Sound 1 and Sound 2, two takes that were edited together for side 2 of the original LP but which are provided in their entirety on the CD. They have the same general form: after a soft melody by the sextet there’s silence, followed by multiphonic saxophone squawks, trumpet smears, trombone whimpers, odd bass figures, and strokes on percussion. Initially unrelated, they growl, stutter and fumble their way to shapes and patterns from which the original melody emerges, to close. Each take charts the evolution of raw sound into music, but so that it’s unclear where one ends and other begins. (CG)

Joseph Jarman – Song For (1967)

Joseph Jarman described Abrams’ Experimental Band as third stream music with a heavy jazz bias, which is a fair summary of much of Jarman’s first album: an inclusiveness characteristic of all the early AACM releases.

It opens with Fred Anderson’s Little Fox Run, typical of much of the avant-garde jazz of the time (nobody yet called it “free jazz”, notwithstanding Ornette’s earlier album of that name). There’s a loosening, but not complete abandonment of the head-solos-head structure that had so long predominated. Jarman’s solos on alto include wide leaps and irregular sometimes compressed, phrasings and the overall balance is deliberately off-kilter due to the use of two drummers, playing flat out. Adam’s Rib has a modernist quality: Stravinskyian in its harmonies, reinforced by Charles Clark’s bass which he plays bowed throughout, some passages entirely in harmonics.

The title track however, is quite definitely what is now thought of as free jazz. It appears aimless, content to explore the circumference of its own space. There is a mournful tune, but it isn’t developed in any conventional sense by the saxophones and trumpet, but is instead modelled into new forms by fragmentation, intonation and register. Surrounding this are a web of sounds: bells, ritualistic chanting, cymbals, even a swanee whistle, and Christopher Gaddy plays his piano from the inside, holding, plucking and hammering strings. Absent a pulse, the drummers provide an undulating curtain of sound. We now call this kind of music “non-linear”, but one can only imagine what it must have sounded like at the time.

For many, poetry with jazz has seldom been successful, but in some cases the problem might be the p-word. Jarman had worked in contemporary musical theatre, and considered as performance art, Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City is a recitation whose flow and peaks are reflected in the changing colours and intensity of the music. The piece might not stand repeated listening (performance art doesn’t really have an afterlife – you had to be there) but it’s an early sign of the theatrical aspect of the Art Ensemble’s performances that were to follow. (CG)

Art Ensemble Of Chicago – People In Sorrow (Pathé Marconi, 1969)

This is one of those albums that completely shifts thinking about music. The unity of vision on this album is uncanny, offering two sides of a slow, almost a-rhythmic flow of immensely sad sounds, coming from a variety of instruments played by Lester Bowie, Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman and Malachi Favors (this is still the period before Famadou Don Moye joined on drums). There is no real soloing, just sounds and phrases interwoven in a stream of music that is both welcoming and strange, with a beautiful theme that once every so often becomes explicit when it emerges out of the background on the first side, and becoming more dominant on the second side, guided by Lester Bowie’s beautiful trumpet playing, over a background of increasing mayhem and ritual shouts and incantations and little percussive sounds and other tribal goodies. Even after all these years, modern listeners will be surprised at the audacity of the music, as much as for its listening relevance today, and hopefully as emotionally impacted as your servant when listening to this album, again and again.

This is an absolute must-have for any fan of free music.Please also note that the early albums of the Art Ensemble of Chicago explicitly mentioned AACM and/or “Great Black Music”. (SG)

Art Ensemble of Chicago: A.A.C.M. Great Black Music – A Jackson in Your House / Message to our Folks / Reese

and the Smooth Ones (BYG Records, 1969 / 2013)

Anthony Braxton – For Alto (Delmark, 1969)

Braxton said that he recorded the album because he always had a love for solo piano compositions, especially for Fats Waller, Arnold Schönberg and Karl-Heinz Stockhausen. But he thought that he “wasn’t strong enough as a pianist to do a solo concert”, which is why he decided to do a solo album for alto saxophone, which he considered his strongest instrument. What’s more, he developed his own vocabulary and syntax for his solo excursions. Braxton dedicated the eight compositions to close friends or musical influences in order to honor the people who’d helped him. The result is a musical stream of consciousness full of overblown and split tones, multiphonics, off-the-wall harmonics, balladesque breath sounds and raw, immediate and compelling energy. A true masterpiece! (MS)

Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre – Humility in the Light

of Creator (Delmark, 1969)

In the liner notes for Humility in the Light of Creator John B. Litweiler calls Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre “a visionary of our times, a William Blake offering his songs in the deadly streets of 1969’s Cities of the Apocalypse”. What made his music so important for the development of the AACM is the fact that he added spirituality to his music, which is why it reminds one of John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders. Especially the integration of the blues as a key aspect and the use of Native American elements by singer George Hines, which makes the album sound like a shaman ritual consisting of dissonant free jazz and African rhythms. And McIntyre’s band is a conglomeration of the future stars of the Chicago scene with Malachi Favors on bass, Thurman Barker and Ajaramu on drums, Leo Smith on trumpet and flugelhorn, John Stubblefield on soprano sax, and Amina Claudine Myers on piano. Humility in the Light of Creator is a perfect example of the AACM approach to create musical freedom through the interplay of silence and sound, it’s an emotional rollercoaster ride, an album which draws its tension from the opposition of density and space. (MS)

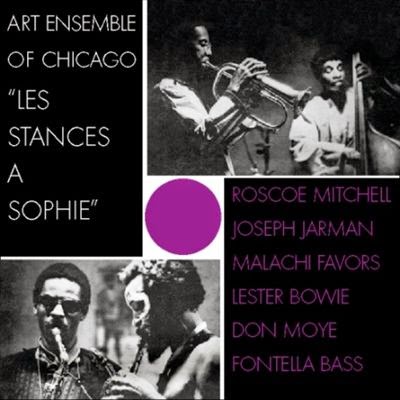

Art Ensemble of Chicago

Les Stances à Sophie (Pathé Marconi, 1970)

Another iconic album by the Art Ensemble of Chicago, originally planned as the soundtrack for a French movie, it was never used for that purpose yet released on the French Pathé Marconi label anyhow. The band consists of Lester Bowie on trumpet, Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman on saxophones, Malachi Favors on bass and Don Moye on drums, but also with Bowie’s wife Fontella bass on vocals. It is iconic because it gives the band a totally new, and probably more accessible sound, and the most fascinating track is the opening composition “Theme de Yoyo”, with lyrics written by Noreen Beasley, sung by Fontella Bass, and as jazz critic Brian Olewnick once described as the “finest fusion of funk and avant-garde jazz ever recorded“. You can listen to it here on Youtube … and if you’re interested, these are the lyrics :

your neck is like the string,

Your body’s like a camembert

oozing from its skin.

floating down the Seine

Your voice is like a long fart (although she may sing “fuck”? on the album)

that’s music to your brain.

that kill what they can’t see

Your hands are like two shovels

digging in me.

Dig, dig, dig, dig it,

On the Champs-Elysees.“

The rest of the album consists of shorter pieces, some very rhythmic, some more meditative, even two variations on a theme by Monteverdi, the beautiful and strange “Thème Amour Universel“, and followed by the even more open-ended “Thème Libre“, a free-minded weird track about which you wonder which film director would use this ever in a movie, and you wonder even more what the scene should look like. The album ends with a short piece with Fontella Bass again on vocals, an unconventional accompaniment by the instruments.

An amazing album. Another one worth mentioning from the same period is the one with French singer Brigitte Fontaine, called “Comme à la Radio“, on which the Art Ensemble accompany her together with Leo Smith. Listen to it on Youtube. (SG)

Revolutionary Ensemble – Vietnam (1972)

After Cooper’s solo winds down at the beginning of side 2, a new scene develops where soundscape rather than personalities predominates: music caught from a distance – a wheezing harmonica, faint wooden flute, and violin (with mute) playing snatches of melody and whispering trills, brought to an end by a mysterious bugle call.

The final section is based on a bluegrass tune – yet another setting to explore. As someone else put it: “All the world’s a stage”. (CG)

Anthony Braxton – The Complete Braxton (Freedom, 1973)

The title might seem an odd description for a musician still in his mid-twenties, but this double-album, recorded over two days in London in 1971, is a display of the range of Braxton’s talents as soloist, duo partner, quartet member and composer. An early sign of his diversity but also aspects of the AACM aesthetic writ large (and they would get larger — Five Tubas is wholly composed, but there must have been something about the sound as Braxton went on to write Composition No. 19 (For 100 Tubas)).

Only Braxton would have thought of combining the style of Schönberg’s piano music with a bluesy saxophone – and make it work – on Soprano Ballad with Chick Corea. Their other duo Up Thing, is a race in technical bravado which Corea probably wins by a head. There’s Contra Basse where he explores all registers of the contrebasse clarinet (again, one of those low instruments that would continue to fascinate Braxton) and he made use of the multi-tracking facilities at Polydor Studios to play all the parts on Four Sopranos.

At the time, Corea and Braxton formed part of Circle, along with Dave Holland (bass) and Barry Altschul (drums, percussion) – one of the great rhythm sections of the 1970s. Substitute Corea with Holland’s friend Kenny Wheeler (trumpet, flugelhorn) and you have the first recordings of Braxton’s great quartet of that decade. There are three tracks, but the rumbustious Be Bop gives a sign of what was to come when the quartet reformed in 1974 to record and tour, and put on some serious muscle. In 1975 Wheeler was replaced by Braxton’s fellow AACM member George Lewis (trombone) and the quartet – and its impossibly fast unisons – continued until 1976. (CG)

Roscoe Mitchell – The Roscoe Mitchell Solo Saxophone Concerts (1974)

The first thing that strikes your eye is the sensational cover on which an arsenal of woodwinds grows like weeds behind a small shack. On his first solo recording Roscoe Mitchell proves to be a brilliant architect of sound and silence, refining simple themes to complex and beautiful tracks. Culled from several different performances Solo Saxophone Concerts presents Mitchell on soprano, alto, tenor and bass saxophones – and on alto in particular he’s a true master. Like his later magnum opus Nonaah from 1977 this album is also bookended by a crude version of his most famous composition by the same name. Solo Saxophone Concerts is an outstanding example of a saxophone solo performance with all its challenges: being out there alone and naked, without any preconceived notions, trying to focus, communicating with yourself, exploring a range of timbres, sounds and emotions (for example in “Oobina”). Solo Saxophone Concerts is Mitchell’s second act of emancipation (after Sound) and at the same time he relentlessly bares his soul. (MS)